How should we feel about Anne-Marie Slaughter and her cover story of the July/August issue of The Atlantic? The piece was headlined “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” a headline that did little to describe the actual content of the story, but helped the piece to explode across the Internet. This story spawned dozens of offspring in the form of think pieces about the content, think pieces about the headline, and think pieces about the image on the cover, a style sometimes referred to as “Sad White Babies With Mean Feminist Mommies.”

How should we feel about Anne-Marie Slaughter and her cover story of the July/August issue of The Atlantic? The piece was headlined “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” a headline that did little to describe the actual content of the story, but helped the piece to explode across the Internet. This story spawned dozens of offspring in the form of think pieces about the content, think pieces about the headline, and think pieces about the image on the cover, a style sometimes referred to as “Sad White Babies With Mean Feminist Mommies.”

How should we feel? Should we think the article was ruined by the headline? Should we be angry at the Atlantic for ruining the story? Should we be impressed at the Atlantic’s savvy Internet marketing strategy*? Should we feel sorry for Slaughter whose piece was mischaracterized by its headline? Should we feel glad for Slaughter, who undoubtedly got more people reading her story, trollgazing, than she would’ve otherwise got?

We can explore the same feelings towards Lena Dunham, who wrote a line of dialogue for her character Hannah about being the voice of “my generation, or a generation,” as a joke, a way to gently undermine her character. The the line was then twisted by HBO’s marketing department, who, in putting together a commercial for the series, pulled the line out of context and made it seem earnest.

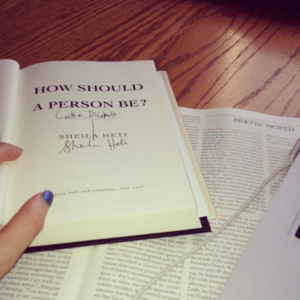

That headline exhausted me, as did that Girls promo spot. This is a new kind of judging a book by its cover: judging a piece of art by the way it’s marketed. Cover-judging still feels awkward, ugly, and lazy. Trying to fight against it seems futile, especially when you have exalted critics like James Wood cover-judging in the pages of The New Yorker. In his review of Sheila Heti’s How Should A Person Be?, Wood criticizes both Heti and her namesake character (Sheila) for wanting to be a celebrity, for her “reality hunger” and for trying to write a play that will change the world. Wood thinks he has to be critical of Heti and Sheila because Heti isn’t being critical of Sheila — but he’s wrong.

Heti writes from Sheila’s perspective about Sheila crying in her cereal if her play does not change the world because Heti is being critical of her character. She’s being critical, and loving, and compassionate at the same time, in the way an author can be about their character in order to create in the reader both a feeling of empathy towards Sheila and an understanding that Sheila does not yet know what she wants. Sheila and most of Heti’s readers live in a culture that values celebrity, and Sheila recognizes that value, while also recognizing the poison in actually being a celebrity. Heti then eloquently expresses Sheila’s struggle over that contradiction, something that is more interesting and starts more conversations than an overall dismissal of celebrity culture.

It’s easy to call Jersey Shore a bad show and point to declining ratings of its spin-offs The Pauly D Project and Snooki & JWOWW as an indication that people are finally understanding how bad these shows are. But that would be wrong, and it would also stop conversation rather than starting it. It’s more interesting to ask, “Why did people love Jersey Shore? Why don’t these same people want to watch the spin-offs?” Exploring the answers to those questions means exploring popular culture in our country, exploring the root of desire, exploring the things that media can and cannot do.

Celebrity culture is something that has such a huge influence over the culture at large that any examination of what it is to be an artist that doesn’t address it is like a person trying to chop an onion with one hand. Wood was so busy insisting that celebrity culture is not worth examining emotionally, he missed the part of the book’s introduction that he should’ve noticed:

Heti starts a new section and begins it: “In an hour Margaux’s going to come over.” Heti was already writing in the present tense, but now she grounds herself in specific moment, the way a boat drops an anchor. Then, Heti writes:

“[Margaux] paints my picture, and I record what she is saying. We do whatever we can to make the other one feel famous.”

At the beginning of her emotional arc, Sheila believes that by recording Margaux, she is making Margaux feel famous. What Sheila does not yet know is that recording Margaux will be the thing that almost undoes their relationship. Margaux feels violated by the recording; Margaux feels betrayed, taken advantage of. Margaux does not feel famous when she is being recorded the way Sheila feels famous when she is being painted. Sheila is wrong.

Wood is criticizing Heti for upholding something that Heti is actually not upholding. Heti finds Sheila’s fame hunger just as flawed as Wood does. The difference is, Wood doesn’t think that exploration has value. Heti does.

*The publication earns more revenue from online advertisements than print ones.

This post may contain affiliate links.