[Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2012]

[Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2012]

“The thing is, I can’t write this book until I get her out of my head,” Alison Bechdel’s comic avatar says to her analyst in the first chapter of Bechdel’s new graphic memoir, Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama. “But the only way to get her out of my head is by writing the book! It’s a paradox.” “Her” indicates Bechdel’s mother, who is securely lodged in Bechdel’s head. It’s not that she’s so terrible, but she makes for a looming psychic presence: intimidating, intellectual, artistically gifted, emotionally remote. She stopped kissing Bechdel good night at age seven, though she was coddling and affectionate with her sons, and seems to have required more nurturing from her daughter than she administered. And so Bechdel hopes to exorcise her mother, she says, as Virginia Woolf exorcised the memories of her parents in writing To the Lighthouse.

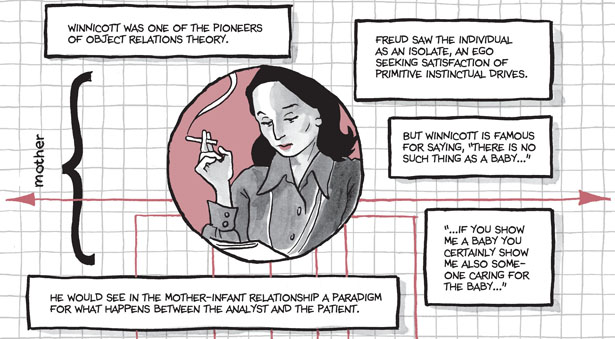

Woolf is one of several threads Bechdel uses to weave the stories, shared and separate, of her and her mother. Other threads include her own therapy sessions, dream interpretation, and the early twentieth century psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. Winnicott’s theories form the key secondary texts for understanding Bechdel’s primary story, but, like Woolf, Winnicott is also a character in his own right. Each chapter opens with one of Bechdel’s dreams, the panels floating over a black background, unfolding into the jumbled fragments of her memories (of her childhood, of romantic and therapeutic relationships spanning twenty years), her mother’s memories, mother and daughter’s present-day conversations, Woolf and Winnicott’s lives, and psychoanalytic theory. Early on she provides an elegant timeline of her lovers and therapists. It’s the sole aid in making chronological sense of a book structured by theme: the chapters have titles like “True and False Self,” “Mind,” and “Hate.”

It’s natural to see Are You My Mother? as the mom-book sequel to Fun Home, Bechdel’s acclaimed 2006 memoir about her father. But their symmetry belies profound differences. On the face of it, Mother is less compelling. The story seems less urgent; it’s less of a story, in fact. Fun Home related the highly blurbable history of Bechdel’s coming out, which catalyzed her father’s coming out, which may have caused him to jump fatally in front of a truck (or was it an accident?). No such tragedy haunts her relationship with her mother, who is still living. But the momentum of this book has other sources — freed from the narrative demands that propelled Fun Home, Bechdel crafts something intricate, internal, tightly woven even as it’s tortuous. Call it Daedalus’s labyrinth, as Bechdel might. If Fun Home was a Jamesian tragedy, as Bechdel styled it, this book is pure modernism. The fragmented, disorienting intersections of the stories, with dreams as the organizing principle, recall T. S. Eliot’s declaration about Ulysses: “Instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythical method.” Are You My Mother? is demanding, as most modernism is demanding.

It’s natural to see Are You My Mother? as the mom-book sequel to Fun Home, Bechdel’s acclaimed 2006 memoir about her father. But their symmetry belies profound differences. On the face of it, Mother is less compelling. The story seems less urgent; it’s less of a story, in fact. Fun Home related the highly blurbable history of Bechdel’s coming out, which catalyzed her father’s coming out, which may have caused him to jump fatally in front of a truck (or was it an accident?). No such tragedy haunts her relationship with her mother, who is still living. But the momentum of this book has other sources — freed from the narrative demands that propelled Fun Home, Bechdel crafts something intricate, internal, tightly woven even as it’s tortuous. Call it Daedalus’s labyrinth, as Bechdel might. If Fun Home was a Jamesian tragedy, as Bechdel styled it, this book is pure modernism. The fragmented, disorienting intersections of the stories, with dreams as the organizing principle, recall T. S. Eliot’s declaration about Ulysses: “Instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythical method.” Are You My Mother? is demanding, as most modernism is demanding.

Mother may disappoint fans of Fun Home, then; I think it is wonderful. I grew annoyed with her mania in Fun Home for comparing her family to every book she’d ever read; the parallels ceased being illuminating and started seeming labored. The literary threads that run through Mother are fewer and sturdier. Woolf appears in the book not merely because Bechdel identifies with her, but as a formal influence. Woolf worried that her stories were merely “essays about [her]self,” and although memoir is inherently an essay about oneself, this one is particularly an essay, sharing in the concerns of Woolf and Winnicott, notably about the self and consciousness. But the heavy quoting of psychoanalytic theory doesn’t feel strained or tedious, at least not to this lover of modernism. And the comic book form works in Bechdel’s favor here: she can simply superimpose Winnicott’s words on a panel depicting her own story, without having to expound the one-to-one correspondence between them.

Bechdel’s invocation of Woolf and the peace she won in writing To the Lighthouse is ultimately heartbreaking. It’s clear she pins similar hopes on her own work (“But the only way to get her out of my head is by writing the book!”). This bid for liberation is especially poignant because it overflows the confines of the book: there is no way to know whether it will work until the book is finished, and so there can be no answer in Are You My Mother? to its most important question. As self-aware as the memoir is — see the dizzying panel in which her mother remarks about the first chapter of the very book you’re reading, “It’s a meta-book!” — there is always one layer beyond its reach. We can see how her mother reacted to the first chapter, but we will never be able to see how she reacts to the last; Bechdel can make her process of writing the book one of its subjects, but can’t, in the book, deliver her final verdict on it. So the question lingers beyond the final page: did she come to peace, as Woolf did, laying her “deeply felt emotions about [her] mother to rest”? Or did she succeed only in transforming her psychic baggage into art? If this is her sole success, it is nevertheless a splendid one.

This post may contain affiliate links.