The Transit of Venus

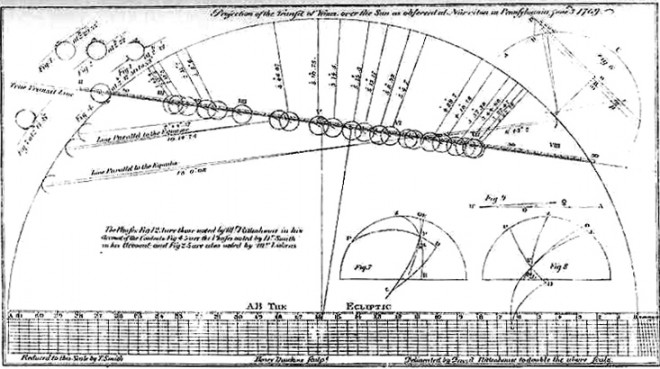

We had originally designated this edition of Full Stop Recommends as “contributors only,” but due to the time-sensitive nature of the transit of Venus I figured our readers could forgive the brief editorial intrusion (and my cutting in line). This evening at around 6pm EST (22:09 UTC) the planet Venus will appear as a small dark disc at the lip of the setting Sun and trace a slow arc as the star descends. The alignment of Earth, Venus, and the Sun is incredibly rare — occurring roughly twice every 115 years — so once the two have dipped below the horizon, that’s it. Venus won’t make another transit until December, 2117. The New York Times likes to point out (twice in this article, geez!) that we’ll all be dead by then. Full Stop would make the counter argument that the NYT is wrong, and we won’t be “dead.” Rather, we will probably exist as incorporeal consciousnesses, stored in servers and used to crunch endless streams of data for the marketing firms of the future, and as such won’t be much interested in the ballet of the heavens.

My point is: come afternoon, climb up on a roof, look west, and watch this thing go down. It’s our last chance as living, breathing human beings! You’ll need special glasses, or a pinhole projector, or a more complicated rig. Whatever you do, remember: your retinas have no pain receptors to tell you “hey, stop;” so, you know, don’t try it.

If you have time, read up the history of past transits — this old sashay is really important, to a degree we owe it our sense of ourselves. If you have a lot of time, read the Cape Town section of Mason & Dixon. If you have your priorities straight, just make sure you’re at a respectable altitude staring responsibly come sundown.

The three recommendations following this one were written by Full Stop contributors and are thorough, oftentimes beautiful suggestions to read and watch and stand hip-deep in the water.

— Jesse Montgomery, Managing Editor

But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz, by Geoff Dyer

But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz, by Geoff Dyer

[Picador; 2009]

As a musician, I’m wary of reading and writing about music. I have no patience for the sonic genealogy that music critics (including yours truly) often have to resort to in order to be understood. When dealing with music’s intangibles, defaulting to something resembling Theosophy is just as tough a pill to swallow. The experience of playing, writing, and hearing music is a difficult one to translate into a concrete medium, and so I was ecstatic when I came across Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz. I tore through the book in a couple sittings, and between reading and my renewed interest in jazz I almost forgot that I had been working as a dog walker, spending my days ankle deep in dog shit.

But Beautiful goes beyond the sound and facts (though Dyer’s command of both is staggering). It’s less “a book about jazz” than a series of portraits: of Charlie Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Duke Ellington and Harry Carney, of Bud Powell, Art Pepper, Lester Young, and others. Jazz just happened to be the way in which they expressed themselves, twanging into the world the thoughts and feelings that lie just beyond words. Dyer’s perspective is contagious: listening to Duke Ellington’s Money Jungle (with Mingus and Max Roach), you can hear Ellington filtering his world through the piano; Mingus “wrestling with the bass.”

The book is divided into vignettes, each featuring one jazz musician; each one a tall tale cobbled together from texts, photos, and recordings. Dyer’s approach to jazz is a lateral one, in the same way that in learning how to play jazz, one learns laterally (i.e. transcribing versions of songs spanning jazz’s 50-plus year lifetime; learning song lyrics; putting the music into a social context). Learning to play and listen like this gives the music a quality of being both outside of time and being time-stamped by multiple eras. Dyer describes this experience beautifully in the illuminating essay at the end of the book: “it is like seeing a photo of your great-grandfather and recognizing the origins of your great-grandchildren’s features in his face.”

Like jazz musicians soloing over standards, Dyer riffs on his sources as if soloing himself. Lester Young standing at his window, watching a parade of his own imitators trolling in and out of Birdland, Mingus on a small bike, each yarn a counterpart to a sound that makes jazz the rich musical language it is.

For Dyer, jazz records are relics left behind by American legends wrestling with their relationships to society and wrestling with themselves. Jazz is “Jazz” with a capital “J” — uniquely American; unique in its pathos. It’s tough not to hear jazz differently after reading But Beautiful. Afterward, every record sounds like a confession to be felt more than understood. It’s the only book I’ve read that made me hear music differently. I wish I would’ve come to it sooner.

Sherlock, created by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat

Sherlock, created by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat

When I first heard that the BBC had set Sherlock — the network’s newest take on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous detective — in the present, with text messages blipping and blog hits tallying, I was skeptical. An admitted devotee of historical fiction, I find the idea of uprooting a perfectly lovely story and transplanting it into the 21st century needless at best and sacrilege at worst.

I have since revised this opinion.

Sherlock is something between a series and a set of six movies; each 90 minute episode is self-contained, though the characters build from one to the next. The first season ran last year on PBS here in the States — it’s now available on Netflix — and the second aired recently enough that you can still watch it on the PBS website (but hurry up!).

Each episode is a craftily re-written version of an earlier Holmes tale, and while many of the plots and characters remain the same, the creators Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat have held to true to essence rather than to detail when necessary. Sherlock is not a pipe-smoking steampunk man caught in the modern age, but a nicotine-patch-covered techie; Watson is a war doctor recently returned from Afghanistan who takes to writing blog posts about their adventures. As much a comedy as a mystery, Sherlock plays up the humor of everything from inconvenient mass texts to Watson’s horror at opening the fridge to find one of Sherlock’s latest experiments.

Steering clear of either a suave yet elusive narcotics addict (as portrayed by Rupert Everett a few years ago on PBS’s Masterpiece) or an aggressively sex-charged Hollywood hunk (as offered by Robert Downey Jr.), Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes resembles an autistic savant whose monumental powers of perception have taken over the neurons usually reserved for social niceties. When Sherlock uses his internalized map of London’s back alleys to chase a car across town on foot, for example, his athletic leaps from one rooftop to the next seem more the result of his lack of physical awareness (combined with conveniently long legs) than an expression of his valiant heroism.

The two leads pair brilliantly. Martin Freeman’s ability to put depth behind Dr. Watson’s deadpan attitude compliments Cumberbatch’s knack for being loveably aloof, and a delightful supporting cast (including Gatiss as Sherlock’s brilliant older brother) further improves on the foundation of Cumberbatch’s and Freeman’s spirited performances.

Our persistent affection for Sherlock has given viewers ample opportunity to see a private detective in action, but, even for those more than familiar with Baskerville’s dratted hounds, this new take on Doyle’s mysteries is not the production to miss. Even as it maintains gripping suspense, it also allows its characters room to develop and play. With a catchy score, an excellent script, and a fitting attention to detail, the BBC’s Sherlock is a perfect romp for those who prefer their mysteries a tad waggish.

My dad has a photograph of my brother and me standing on a mound of dirt, the excavated basement of his new house. The foundation has been poured and the first walls framed. To the east, behind the photographer, a field of knee-high-by-the-fourth-of-July corn stretched to the horizon. To the north and west, behind my brother and me, the heart of Wisconsin’s “driftless area,” a swath of unglaciated landscape so wild that even today it is nesting ground for wary and fragile sandhill and maybe even whooping cranes.

There is another photograph of my brother and me standing near an enormous boulder, a glacier-polished pearl of granite the home builders had to deal with to put up the house. The photograph is some thirty years old and captures something more than the beginning of my dad’s new life — my parents had recently divorced. What the Wisconsin glacier couldn’t accomplish 12,000 years ago is slowly being achieved by end-loaders, bull-dozers, earth movers, subdivisions, and a different sort of crane — the necky, metallic monsters erecting tall buildings cutting a jagged silhouette into the sky. Those balls of granite mark the terminal moraine of the Wisconsin glacier, bits of rock gouged from the continental shelf and carried south by a wall of ice.

In all the summers I spent at Dad’s while growing up, we encountered no more than thirty cars at the intersection of County Highway M and Cross Country Road near his new house. Thirty cars in fifteen years! This past week we waited that many minutes for all the traffic at that same intersection.

Despite this, I want you to go there. I want you there because I believe, paradoxically, that in going there you will be able to save this place. But you need some perspective, a way of seeing which too few have. Get an orange or imagine one. Roll it in your hands. Toss it in the air and catch it. Slide your thumb over its waxy skin. Draw a pea-sized circle on it. That is the Driftless. You are still not seeing it, though.

Look at the skin, its wrinkled surface. The high spots are the ridge tops, and bluffs. Look down in the creases, slide your nail into one. At the bottom of each of those coulees is a vein of water, gin clear and cold, sheathed in a tube of willow swamp and marsh. Tighten your focus even deeper, even smaller. There, finning in an eddy, sulking under a cut bank, rising to sip a mayfly from the surface film, is a trout.

As we have done for a dozen years, my dad and I have just explored some of those coulees and creeks with fishing gear. On our last morning, we drove out from his house on some state highway. We dropped down off the ridge top on some county truck. As we switch-backed our way into the coulee and back in time, Dad said, “I love it when the fog fills the valley like that.” I know. Me too.

Standing shin-deep in the flow, blue-winged olive mayflies like pixie dust in the air, I set an olive imitation lightly into the current and was allowed one more precious conversation with a trout. I learned that trout is not a trout at all. It is a unicorn, Loch Ness. It is Atlantis. It is the fountain of youth. It is the balm to soothe the wounds of divorce. It is the catalyst for conversations you have been avoiding. It is friendship. It is love.

I want you to go there. When you go, take a fly rod. If you suffer enough, when you get your mind right, that fish will take your fly. Listen to what he says!

This post may contain affiliate links.