[Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2012]

[Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2012]

Tr. from German by Alan Bance

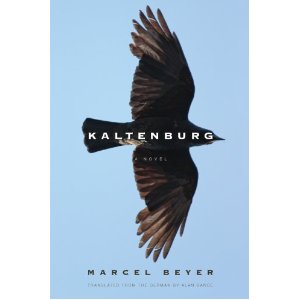

Flight — the relationship between heft and lift — underpins Marcel Beyer’s retelling of the Konrad Lorenz story, Kaltenburg. First published in German in 2008, the novel finally appears in English. Alan Bance has done an admirable translation for the up-and-coming German author, and the result is a lyrical, somewhat conventional novelistic taxonomy: a chronicle of ornithological types that mingles acute scientific observation with the trauma of the Dresden bombings and the memory of Nazi Germany.

It was in 1963 that Konrad Lorenz, the renowned zoologist and ethologist, opened his tract On Aggression with the bold declaration, “My childhood dream of flying is realized” (“Der alte Traum vom Fliegen hat sich verwirklicht”). To fly, for Lorenz, was not to escape but rather to imitate, participate in, and decipher the hieroglyphs of animal communication. Beyer seizes on this understanding of flight as he re-envisions Lorenz’s classic explorations of the psyche of jackdaws and greylag geese (which now shape the basis for imprinting, group selection, and motivation theory). That Lorenz’s observations of flight were at the forefront of psychology and biology at a time when sinister political forces were looking for particular justifications complicated matters — especially those related to his legacy. This is the topography Beyer resolutely takes on. Kaltenburg intuits Sebaldian preoccupations with memory and trauma, yet it rises to its subject of Lorenz’s legacy with levity and a touch of youthful curiosity. This is neither Houellebecq’s representational experimenting nor an “information novel”; instead, it is a novel where science compliments a somewhat traditional yet well-wrought narrative arc.

The book is driven by its narrator, Hermann Funk, who describes to a female translator his life as an ornithologist under the tutelage of the notorious Kaltenburg, Beyer’s stand-in for Lorenz. Funk’s perspective is a welcome one; it is his fascination with Great Auks and Sea Cows (long extinct species) that fills the otherwise foreboding novel with a sense of wonderment and discovery. In other words, Funk’s obsession with the ineffable magic of animals gives life — and wings — to the work. The novel follows the same process that Funk and Kaltenburg practice during their long walks along the Elbe: “induction by personal inspection.” In the world of Kaltenburg, “personal inspection” is tethered to what is apparently a concrete natural reality. Of Kaltenburg’s popularity, Funk explains:

[The audience] found it refreshing that someone was talking purely about observations, solid information, irrefutable facts which no reasonable person could doubt.

Kaltenburg itself deals repeatedly with “solid information.” However, the “irrefutable facts” of the novel fail to satiate: as Funk teaches the nomenclature of local birds to the translator, German, English, Linnaean, and Russian terms overwhelm the student — and the reader. (Though it is fun to learn those geese actually are called Anser anser.) Yet even these concrete terms prove slippery terrain: Kaltenburg’s trips to the Soviet Union and meetings with Nazi officials impact Funk’s lingual preferences. The historical circumstances which pervade the novel become embedded into what is supposed to be an ironclad terminology. Facts are fraught with political meaning, and ornithological taxonomies become a paean to indeterminacy.

Kaltenburg pictures the wreckage of Dresden after its bombing, yet manages to eschew trite sentimentality. The “dead zones” of the city become an engaging (albeit corpse-infested) playground for children:

Together we combed through the dead zones in the inner city, all children were drawn like magic to the rubble . . . The real challenge lay in finding your way about after dark, which was obviously forbidden.

Most haunting of all is the prospect of losing one’s perceptive abilities. Upon encountering a man with an eye-patch amidst the rubble, a gang of children pelts him with rocks. Vision is the key here, as it is for much of the novel. The great ethologist, Kaltenburg himself finds his perceptual acuity occluded under the penetrating gaze of Stalin (who peers out from omnipresent portraits Kaltenburg remembers from his murky time in the Soviet Union). A darker history swirls around the text as Kaltenburg negotiates the Nazi Party and the specter of Stalin, but power and observation (“No, the zones didn’t seem dead to us then.”) ultimately drive the history of the “Great Garden,” the site where the narrator witnessed the bombings.

Kaltenburg is finally a man with a simple principle: “To live is to observe.” Yet for Funk, Kaltenburg enacts the nurturing, educative example they so often record in animals during their observing trips — the taking under one’s wing. Funk’s perspective is an alternative history, both of Dresden and of the fictional ethologist modeled on Lorenz.

While “Ideologists put nooses around each other’s necks,” Funk’s wife reads Proust. And while the male ornithologists obsessively reflect on Kaltenburg’s reputation Funk’s wife delivers a separate, perhaps more nuanced, perspective. Her engagement with Proust has taken her out of the realm of the scientific fact, something Beyer seems keen to highlight. Lorenz told through the lens of history tells one story. Told through Beyer’s Proustian lens, however, the ethologist becomes something else entirely — something at once more human, more sinister, and more bewildering. It is this — the re-imagined human text — that makes Beyer’s taxonomic novel so compelling.

This post may contain affiliate links.