Maurice Sendak, who died on Monday, was awarded a Caldecott Medal for Where the Wild Things Are nearly 50 years ago. In his acceptance speech (which is worth reading in its entirety), Sendak describes witnessing children playing on the street in front of his parents’ house in Brooklyn. They’re playing a game in which one child turns himself into a “howling, groaning, hunched horror” and chases four giggling girls, “willing victims,” around the street. Sendak notes that such games are extraordinarily common, and “are the necessary games children must conjure up to combat an awful fact of childhood: the fact of their vulnerability to fear, anger, hate, frustration — all the emotions that are an ordinary part of their lives and that they can perceive only as ungovernable and dangerous forces. To master these forces, children turn to fantasy: that imagined world where disturbing emotional situations are solved to their satisfaction. Through fantasy, Max, the hero of my book, discharges his anger against his mother, and returns to the real world sleepy, hungry, and at peace with himself.”

Sendak goes on to describe the unwillingness of adults to acknowledge the darkness inherent to children’s experience, and denounces some other children’s books’ presentation of a “gilded world unshadowed by the least suggestion of conflict or pain, a world manufactured by those who cannot — who don’t care to — remember the truth of their own childhood.” He goes on to say, “The need for evasive books is the most obvious indication of the common wish to protect children from their everyday fears and anxieties, a hopeless wish that denies the child’s endless battle with disturbing emotions.” Rather than deny a child their battle, Sendak jubilantly leads them forward.

Sendak is occasionally mentioned in the same breath with Roald Dahl — both men being authors of children’s books that explore unusually dark, fantastical themes. But to equate them is to misunderstand them both: Dahl’s darkness lay in a particular obsession with exploring and ultimately conquering the sociopathy of the school-age bully (and one needs only to read a few chapters of Boy to understand the excruciating life experiences Dahl was inspired by), while Sendak’s darkness was a more intuitive exploration of the role fantasy plays in the life of a child. I owe an imaginative childhood to both writers, but my debt to Dahl is significantly different than my debt to Sendak.

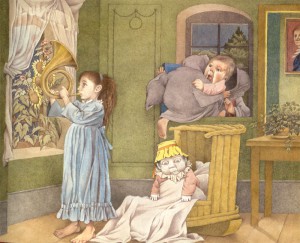

When I was a child, one of my favorite books was Sendak’s Outside Over There. The book’s rich illustrations, while recognizably Sendak’s, seem to owe more to renaissance painting than do the sparer sketches that define Sendak’s earlier books, like Pierre: A Cautionary Tale and The Sign on Rosie’s Door. I didn’t realize that the book was by Sendak until I was much older, and so it existed for me as an anomaly; a kind of secret treasure: a magic, magnetic story that I saved for reading only every so often, not wanting the weird tale to lose its power.

Outside Over There inspired Jim Henson’s The Labyrinth, so you’ll likely recognize its plot: Ida, the older sister, is supposed to be watching her baby sister while her father, a sailor, is out to sea. But the baby is stolen by goblins when Ida isn’t looking (bored by her babysitting duties, she’s playing her “wonder horn”) and replaced by a terrifying, goulish-looking changeling made of ice. Ida doesn’t notice the difference until the ice baby melts, which is when she realizes the goblins have stolen her sister to “be a nasty goblin’s bride.” She takes off in her mother’s raincoat with her wonder horn tucked in the pocket, to make “a serious mistake” — falling backwards out the window, into outside, over there. Flying backwards through the air, she almost misses her sister until her father’s voice, carried over the sea to her ears, directs her to turn around. She turns and lands in the middle of the goblin’s wedding — the goblins turning out, bizarrely, to be just babies, like her sister — where she plays a sailor’s jig on her wonder horn, which causes the baby-goblins to dance until they churn themselves into a stream of water, which flows away. She brings her sister back to her mother, who is reading a letter from her sailor father, telling Ida he will be home “one day” and to look after her mother and her sister until he returns — “which is just what Ida did.”

Outside Over There inspired Jim Henson’s The Labyrinth, so you’ll likely recognize its plot: Ida, the older sister, is supposed to be watching her baby sister while her father, a sailor, is out to sea. But the baby is stolen by goblins when Ida isn’t looking (bored by her babysitting duties, she’s playing her “wonder horn”) and replaced by a terrifying, goulish-looking changeling made of ice. Ida doesn’t notice the difference until the ice baby melts, which is when she realizes the goblins have stolen her sister to “be a nasty goblin’s bride.” She takes off in her mother’s raincoat with her wonder horn tucked in the pocket, to make “a serious mistake” — falling backwards out the window, into outside, over there. Flying backwards through the air, she almost misses her sister until her father’s voice, carried over the sea to her ears, directs her to turn around. She turns and lands in the middle of the goblin’s wedding — the goblins turning out, bizarrely, to be just babies, like her sister — where she plays a sailor’s jig on her wonder horn, which causes the baby-goblins to dance until they churn themselves into a stream of water, which flows away. She brings her sister back to her mother, who is reading a letter from her sailor father, telling Ida he will be home “one day” and to look after her mother and her sister until he returns — “which is just what Ida did.”

Sendak’s tales are often surprisingly complex, but a central theme is a desire for escape — Rosie wants to escape boredom; Max wants to escape his anger; Ida wants to escape responsibility. Rather than escaping their feelings, of course, the characters delve into them. They travel through their respective imaginations and magical outsides, over theres; they turn themselves into singers and kings and musicians, possibly getting eaten by a lion (Pierre) or baked into a cake (In the Night Kitchen) in the process, but always playing or dancing or wildly tangling with the beasts of their feelings. The characters inevitably return to the “real world” happy, exhausted, satiated — although their situations remain essentially unchanged. They find resolution through imagination, just as a child makes sense of the world through a game of pretend.

What I remember most of Outside Over There is how enthralled I was by its eery illustrations and frightening storyline — the terrifying ice baby, the faceless goblins, the weird concept of a baby-goblin wedding, the evocation of my childhood fear of being kidnapped — and the distant comfort of Ida’s absent father.  He redirects her, from far away, during her flight to the goblin’s hide-out, and his directive to take responsibility at the end of the book is one that she finally, and happily, accepts. When I was a child and my own father was away traveling, as (it felt like) he often was, I wished that he, too, would give me direction in absentia, and accompany me through both my long-winded games of pretend and the burdensome real world, in which I felt an unusual responsibility for my three unruly younger siblings.

He redirects her, from far away, during her flight to the goblin’s hide-out, and his directive to take responsibility at the end of the book is one that she finally, and happily, accepts. When I was a child and my own father was away traveling, as (it felt like) he often was, I wished that he, too, would give me direction in absentia, and accompany me through both my long-winded games of pretend and the burdensome real world, in which I felt an unusual responsibility for my three unruly younger siblings.

Of course, such direction and company is what Sendak’s work has offered generations of children: like the sailor-father in Outside, Over There, his voice leads children through the darkest thickets of their imagination, telling them where to take the right turn (especially when the right turn is the wrong one) to have a riotous adventure. In an interview on NPR’s Fresh Air last year, Sendak said, “There are so many beautiful things in the world which I will have to leave when I die, but I’m ready, I’m ready, I’m ready.” Like all of his characters, he was ready to leave; and he has left so many beautiful things for the rest of us.

This post may contain affiliate links.