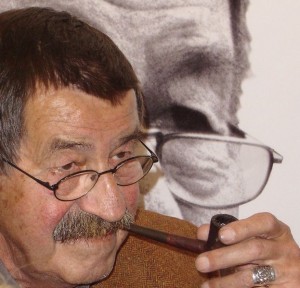

As if to celebrate America’s National Poetry Month, German Nobel Laureate Günter Grass took to the pages of Der Spiegel last Wednesday to prove, contra popular claims, poetry’s continuing relevance. Yet Grass’s poem, a vociferous condemnation of Israeli policy towards Iran entitled “What Must Be Said,” also revealed a major flaw of so much contemporary political literature.

As if to celebrate America’s National Poetry Month, German Nobel Laureate Günter Grass took to the pages of Der Spiegel last Wednesday to prove, contra popular claims, poetry’s continuing relevance. Yet Grass’s poem, a vociferous condemnation of Israeli policy towards Iran entitled “What Must Be Said,” also revealed a major flaw of so much contemporary political literature.

Israel remains a fraught issue, prone to attracting some very ugly and primordial hatreds. A German criticizing Israel dredges up some truly awful reminisces, especially when the German in question is a former Waffen-SS trooper who had kept his service a secret for over six decades. Not surprising, then, that the reaction proved to as vociferous as the poem — the Israeli embassy accused Grass of blood libel, and Israeli Interior Minister Eli Yishai slapped Grass with a travel ban to boot. Grass even faced condemnation from his own foreign minister, Guido Westerwelle, who called Grass’s purported moral equivalency between Israel and Iran “absurd.” Others seized on Grass’s aforementioned service in the Second World War, calling Grass a “former Nazi penning a rationalization of a regime that promotes a similar style of hate for Jews.” This, despite Grass’s acknowledgement in the poem of “my own origins/Tarnished by a stain that can never be removed.” Indeed, the recurring theme of silence suggests that Grass is purposefully talking around his own past, mirroring — and feebly excusing — his years of denial.

Conspicuous in its absence from the discussion, however, is this simple fact: the poem is lousy. It’s not just that “submarine” scans poorly into poetical meter — although it does, obviously — it’s that the whole tone of the poem seems weirdly off. With its discussion of nuclear inspections and arms sales, it reads like an Intro to IR lecture given in haiku. While the words hint at myriad poetic possibilities — historical guilt, nuclear annihilation, state violence — Grass is content to treat the poem as a political manifesto with line breaks. Grass promisingly describes the Iranian people “subjugated by a loudmouth/And gathered in organized rallies” — hinting at a parallel between Iran’s present and Germany’s past — but the poem nevertheless devolves into a series of observations that become painfully banal. If we accept the maxim ars longa, vita brevis then this sure as hell isn’t art: its plainness and limited scope tie it to a distinct political moment. In his rush to issue a (worthwhile) political opinion, Grass forgets to make his poem a poem. “The Masque of Anarchy,” in other words, this ain’t.

Independent of the thorny politics, then, Grass’s poem reveals a tension between literature and political writing. In a recent essay, Egyptian poet Yahyia Lababidi notes that art at its best creates a clarifying distance, perceiving the whole of a crucial moment in ways denied to its participants. To take an example, Larkin’s “MCMXIV” works because of the historical distance between the event portrayed — a bank holiday in the summer of 1914, right before the outbreak of the Great War — and Larkin’s writing of the poem in 1964. The poem’s foreboding sense of the death of innocence, indeed, relies on a half-century of hindsight. By contrast, Grass struggles to establish the sort of distance Lababidi hopes for — the few moments when Grass takes a long view are awkwardly scattershot, diversions from the political thrust. The Nobel Laureate struggles to fully integrate the present moment and its human actors into the larger bend of history, and in the end falls short. From the author of The Tin Drum, who is writing in a distressingly dehumanizing political discourse, it’s a disappointing failure.

This post may contain affiliate links.