‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

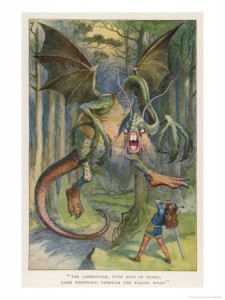

So begins Lewis Carroll’s poem Jabberwocky, ostensibly a “nonsense” poem contained within Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, describing the hunting and slaying of an infamous and monstrous beast. It is a fantastic piece of writing, filled with strange and evocative imagery, and yet it contains many words which don’t exist in the English language. Despite this (or perhaps because of it), the reader is still able to understand perfectly the meaning of the poem. Carroll’s “nonsense” is not just random letters thrown together to make strange words. Instead, his unique talent for using logic in a non-logical setting comes to the fore in the poem, as he makes excellent use of onomatopoeia and association in order to convey meaning. Thus, many of the words are very similar to conventional descriptive words — for example, brillig has the sound of a chill about it, slithy reflects “slimy”, “slither” and “lithe” and wabe evokes associations with “wave” and “ebb”.

The effect of this is to make the key to the meaning of the poem actually in the imagination of the reader. This perhaps reflects the status of Through the Looking-Glass as a children’s book, since sounds are always an important factor in children’s language learning. Most importantly, the association between the sounds of the nonsense words and their “real world” counterparts helps to solidify meaning without limiting it to a fixed interpretation. It is expressing rather than defining, yet without being too vague, and it expands the richness of the language and fuels the imagination. In a sense it is linguistic brain-training at its best.

Contrast Carroll’s approach with Orwell’s description of the language of Newspeak in the appendix of 1984. Here, language is controlled and proscribed in order to restrict meaning (and by extension thought) to a certain model or interpretation. Far from creating new words, the number of words is actually being reduced. Removal of “superfluous” words which are derivatives or close associations of other words (thus words which Carroll relied on for his meaning in Jabberwocky) narrows the field of interpretation to a fixed, unmoving point. Thus words such as “awful”, “terrible” or “monstrous” are constricted to “ungood”, simply the opposite of “good”. Of course, this process leaves behind a much less descriptive word which conveys almost no emotion and requires no imagination to interpret. It becomes a vague idea of something that is simply “not good”.

Interestingly, a similar technique to that described by Orwell is often used in political speeches. Of course, words are not actually deleted from the language, but certain words are not said, or only said in certain contexts and others are used repetitively. The constant use and re-use of certain words and stock phrases is a defining characteristic of the average political speech of any hue. They are repeated, mantra-like until they become devoid of almost all meaning, or become associated with only one narrow and vague meaning, much like Orwell’s “ungood”. This acts as a barrier to imaginative thought as well as a disincentive to debate. This phenomenon has been noted by several commentators over the years (including Orwell himself in his essay Politics and the English Language), but the following clip from the excellent British satirist Armando Iannucci sums up the point most succinctly:

(Starts at 1:10)

So embrace the nonsense, because on this scale of language and thought, the words of Carroll’s whimsical poetry are actually more truthful than the words of many of our politicians. But then, you probably knew that anyway…

This post may contain affiliate links.