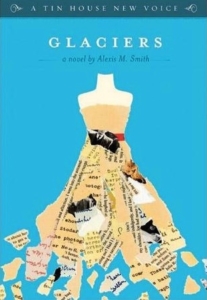

In order to consider Glaciers, Portlander and former Powell’s bookslinger Alexis M. Smith’s first novel, we must first consider what it is not. On the cover, the slender white shoulders of a dressmaker’s dummy peek out from a strapless dress made from scraps of black and white photographs and yellowed letters; on the back, “single,” “twenty-something,” “unrequited love,” “the perfect vintage dress” jump out from the summary. The problem? Glaciers looks like chick lit. But it isn’t.

I am not here to champion or disparage this particular genre — I only want to say that Glaciers simply does not belong there. There is romance, yes, but it does not play out in the way that the cover might lead one to expect. Perhaps it is fundamentally unfair to book designers that a novel that features a dress cannot have one on its cover, but other authors have suffered the same fate and it dooms their books to an unfortunate paradox: readers who dislike “chick lit” won’t buy the book, and the ones who expect a race to a romantic finish will be disappointed. Glaciers is published by Tin House, a small press better known for its renowned literary magazine and writing workshops, and perhaps the design is meant to give the book an edge against larger publishers. This is massively unfair to Smith and her readers — Glaciers, although it has its flaws, is a subtle and beautifully written book, and it would be a pity if its design drove anyone away.

In Glaciers, the events of a single day in professional book-mender and thrift-shopper Isabel’s life are interwoven (à la Mrs. Dalloway) with glimpses of her childhood in Alaska among the titular glaciers and with the futures she imagines for herself. In particular, she fixates on an antique postcard from an anonymous man in Amsterdam, inscribed with a romantic and haunting message — “You are all that I see when I open a book.” She wonders what her life would be if she lived in Amsterdam instead of Portland, deftly described as “a slick fog of a city…drenched in itself.”

Her interest in acquiring the pre-owned raises questions about why these objects are so much more evocative than things from her own era. Questions that she never faces head on. As a child, Isabel’s collection of old photographs, salvaged from a thrift shop, moved with her from city to city as she coped with her parents divorce:

The people in the photographs came to mean as much to her as her own relatives. She had rescued them in her Alaska, her home, and carried them with her into a new life in the city. She imagined them looking in on her from the afterlife, grateful, watching over her. She would occasionally climb the maple tree in her yard and look up at the sky, trying to imagine a time when her own existence, her clothes and haircut, and the saturated colors of their family snapshots, would be antique. She knew that it would happen, but she could not imagine what the future might look like, or what her place might be in it.

This kind of self-awareness is rare within the novel; the focus is on the small events of Isabel’s life, not her feelings about them.

In fact, all of her reminiscences can be characterized by a lightness, as if Smith is hesitant to put anything too disagreeable into Isabel’s world of beautiful things. Reading Glaciers is a bit like having a self-conscious friend, reluctant to reveal anything too personal, too embarrassing, too human. Even in scenes intended to be unpleasant, Isabel’s loveliness remains unruffled:

A small cockroach walked down the wall nearly to their table…They watched it throughout the meal with good-humored detachment, calling her Oolong and addressing her in conversation.

Her relationship with her best friend Leo feels similarly precious — they speak in a way that feels too seamless and chummy to be authentic. The two of them discuss Isabel’s work crush:

I need your help, she blurts.

In trouble already? It’s barely lunch, girl.

I’m on a break, she says.

Oh, he says, I see. Wolf or woodsman?

Woodsman.

The one?

The same.

Oh, Bell, he says, sighing.

I know.

Tough love or shoulder to cry on?

Let me have it, please.

The nicknames (she calls him “Loon”), the fairy-tale in-jokes, the dialogue that doesn’t miss a beat — I doubt whether these people are talking about anything at all. The shallow gay friend is an insulting cliché, but worse is the stereotype of the woman whose friendships are too flimsy to bear the weight of anything more substantial than boy-talk. Also curiously absent is any mention of Isabel’s sexuality, even as she pursues her “woodsman.” In such a deliberately sexless world, allusions to the vaguely erotic — the word “panties,” for instance, or the presence of an adult bookshop — feel strangely inappropriate, especially juxtaposed with so many childhood memories.

Perhaps this is the fate of the diurnal novel: in its haste to collect the day’s ephemera, Glaciers can only skim the surface of Isabel’s character. There are depths worth plumbing — Isabel’s feelings about the Iraq war, which features prominently, or the impending demise of the glaciers of her childhood — but as Smith writes:

Isabel cannot read magazine articles or books about the North. She cannot watch the nature programs about the migrations of birds and mammals dwindling, the sea ice thinning…she does not want to know what has happened to her great-grandmother’s house by the woods, sold years ago to people who let gutted cars rot in the front yard.

It is Isabel’s refusal to face these truths that define her character. Although her lack of growth is frustrating, it is true that Smith’s descriptive abilities still make the book an aesthetic pleasure, even if her considerable illustrative talents would better serve a more compelling character.

This post may contain affiliate links.