David Ives’ Venus in Fur opens on a sparsely furnished audition room in New York City. Poorly lit by fluorescent lights, frustrated, and talking on his cell phone, the play’s male lead Thomas Novachek (played by Hugh Dancy in the show’s Broadway production this year) complains that there are no — literally, no — women to play his leading lady. Thomas, who’s written and plans to direct a stage adaptation of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s (in)famous novel Venus in Furs, is apparently at his wits’ end. “There are no women like this,” he says, “no young women, or young-ish women. No beautiful-slash-sexy women.” He continues,

No sexy-slash-articulate young women with some classical training and a particle of brain in their skulls. Is that so much to ask? An actress who can actually pronounce the word “degradation” without a tutor?”

Before this bit of irony sinks in, cue — in true theatrical fashion — an ominous roll of thunder as he describes the actresses: prop-toting, unfeminine (“Half are dressed like hookers, half like dykes,” he says), and, worst of all, desperate. And then — a knock on the door. Enter Vanda Jordan (Nina Arianda), an unrefined, frantic actress with a bag full of props who has missed her audition hours ago. What follows these opening moments is hard to define. On one hand, Venus in Fur could easily be an audition narrative in which Vanda, a girl with no chance of landing the big gig, proves herself to a doubtful director; on the other, it is a wonderfully dark exploration of power relationships and transgressive desire on par with Miss Julie. More likely, though, the play is neither — instead, it asks us to reconsider the subtler, more ambiguous and unsettling possibility that many iterations of subversion come with their own forms of injustice.

The novel Venus in Furs, and Thomas’ adaptation in the play that the characters read together onstage, imagines Vanda Dunayev as a woman transformed into a cruel dominatrix through her relationship with the willingly submissive Severin Kushemski. Pleading with Dunayev to overpower him, Kushemski says, “This is the future of men and women. Let the one who would kneel, kneel. Let the one who would submit anyway, submit now.” Desperate to find a woman — the woman — who can embrace and live out his transgressive desire, Kushemski frets that he is destined to live in misery until he meets the hedonist Dunayev. His submission to her, however, is tempered by his fierce and overpowering desire to transform Dunayev into his idol, the goddess Venus:

This Venus is the most beautiful woman I have ever seen. I love her madly, passionately, with feverish intensity, as one can only love a woman who responds to one with a petrified smile, ever calm and unchanging. I adore her absolutely.

Convinced of her ability to dominate him completely (despite her protestation), and intrigued by her likeness, both physically and intellectually, to his revered goddess, Kushemski is at once mesmerized by Dunayev and, ultimately, driven mad by her infidelity. To transform woman into goddess – to definitively upend the relationship between man and woman — is Kushemski’s, and, perhaps, Thomas’, most deep-seated desire. But it is one rife with inconsistencies: at their cores, both Kushemski and Thomas are blind to the reality that neither Dunayev nor Vanda are the goddess they so willingly conjure.

But as Vanda and Thomas read the lines of the play-within-a-play as Dunayev and Kushemski, their electric dialogue — both as Vanda and Thomas and as their characters — belies the notion that the play is simply about overturning the power structure inherent in what we perceive as the actor-director relationship, or in that of woman to man, wife to husband, or submissive to dominant. Transgression, at least the easy transgression of Kushemski’s imagination, is simply not enough to explain these relationships. Indeed, Thomas — along with the audience — becomes increasingly, and at times frighteningly, aware that Vanda is more than an auditioning actress with an incredible talent; as their reading becomes more and more intense, Vanda begins to question the motivations behind the play’s very subversion:

THOMAS: To me, this is a play about two people who are joined irreparably. They’re handcuffed at the heart.

VANDA: Yeah, joined by his kink.

THOMAS: No. By their passion.

VANDA: His passion.

THOMAS: You’re denying her passion. That’s sexist, too. She’s as passionate as he is, and this play is about how these two passions collide.

VANDA: What age are you living in? He brings her into this, and she’s the one who gets to look bad, she’s the villain.

By the end of the play, Vanda’s questions have transformed into all-out rage:

How dare you? How DARE you! You thought you could dupe some poor, willing, idiot actress and bend her to your program, didn’t you. Create your own little female Frankenstein monster. You thought that you could use me to insult me?

As she achieves true domination over Thomas (giving away too much here would, of course, spoil the fun of seeing it performed),  Vanda’s total transformation from her first lines is nothing less than spectacular. She seems to embody — both literally in an “improvised” scene and symbolically — the goddess that Thomas and Kushemski desire. But whether she is uncannily adept at transforming from “ditz to dominatrix,” bent on undermining the power relationships of the audition process, or in fact Venus herself come to enlighten — or punish — Thomas, the audience is confronted with a play that asks us to consider more deeply our expectations and our judgments. If we are serious about considering power and gender, we are required to reject cookie-cutter subversions of power relationships; the failure to do so, the play suggests, will accomplish nothing but reinforcing once again Thomas’ and Kushemski’s destructive goddess worship. The significance of a show like Venus in Fur is that it turns the tables deftly on the audience while simultaneously understanding itself as a testament to the ways in which power has so totally infiltrated the arts experience.

Vanda’s total transformation from her first lines is nothing less than spectacular. She seems to embody — both literally in an “improvised” scene and symbolically — the goddess that Thomas and Kushemski desire. But whether she is uncannily adept at transforming from “ditz to dominatrix,” bent on undermining the power relationships of the audition process, or in fact Venus herself come to enlighten — or punish — Thomas, the audience is confronted with a play that asks us to consider more deeply our expectations and our judgments. If we are serious about considering power and gender, we are required to reject cookie-cutter subversions of power relationships; the failure to do so, the play suggests, will accomplish nothing but reinforcing once again Thomas’ and Kushemski’s destructive goddess worship. The significance of a show like Venus in Fur is that it turns the tables deftly on the audience while simultaneously understanding itself as a testament to the ways in which power has so totally infiltrated the arts experience.

Venus in Fur, which opened off-Broadway in 2010, received immediate and intense critical acclaim, at least in part due to Arianda’s electrifying performance as Vanda. Rave reviews from top theater critics nationwide extended the show’s performance twice, and are at least partially responsible for its revival (only a year later) on Broadway, which has also been extended. Yet innate in all the hype surrounding the show is what is at best a fundamental inability to express some of the deepest, most compelling truths in the play, and at worst a willful ignorance of what it offers. On one hand are distillations of the plot into palatable, simplistic synopses; on the other, profiles of Arianda’s incredible rise from unknown NYU-grad to Broadway’s “next big thing.” Both, ultimately, bear striking resemblance to the very narrative genericism that the play seeks to undermine.

In his November 7, 2011 profile of Nina Arianda, The New Yorker’s John Lahr — and the many producers, directors, and writers he interviewed — compared the actress’ talent to a litany of stage legends: in the article, Barbara Harris, Zoe Caldwell, Barbara Streisand, Judy Holiday, and Meryl Streep each provide easy analogies to Arianda’s astonishing and meteoric rise. Describing her audition, Lahr writes,

Just before Arianda walked into the room, her resume was passed to Brian Kulick, the artistic director of the Classic Stage Company, who was planning to produce the play. Next to Kulick at the table were David Ives and the director Walter Bobbie […]. Kulick glanced down at Aridanda’s lean C.V. “I’m gonna kill James,” he said to Ives. “This is a waste of my time.” Arianda entered the audition room with her bag of props, just as Vanda does in the script, and performed the first seven minutes of the play. “She didn’t just read the lines as a character,” Bobbie recalled. “She brought the entire script to life.” […]

Bobbie wanted to stop the auditions immediately. “She showed me how the play worked,” he said. “I was afraid someone would cast her by the end of the day. It was that breathtaking an audition. I don’t know how to explain it. But when the real thing walks in the room you know it.” On her audition sheet, below where Paul Davis had written “Bold. Sexy. Funny,” Calleri scribbled “STW” – Straight to Wardrobe.

It’s the kind of description you might expect from Thomas Novachek, raving that his very own dominating Venus has walked in the door to give the audition of a lifetime on a dark and stormy night. Indeed, Lahr figures Arianda’s talent and discovery in terms of these stars presumably to indicate the nature of Arianda’s explosive debut, yet in the context of Venus in Fur’s resistance to our tendency to imbue women with this exact cosmic quality, the description falls flat. Consider again the actresses to whom Arianda has been compared, those paradigms of our arts culture that govern our expectations and give our critical narratives such rigidity. Are these goddesses? Perhaps not, but the language with which we define a woman’s talent — “Bold. Sexy. Funny.” — speaks volumes about the underlying truth of Ives’ play. Our ability to even consider a great performance is, indeed, colored by the language of the power structure Vanda ultimately dismantles on stage. What Lahr’s profile fails to address is Arianda’s profound understanding of the troubling and simplistic way in which we understand women, femininity, and power in art. If Venus in Fur attempts to expose an underlying weakness in the critical medium to tend to problems of power in artistic culture, then it appears as though it has done its job.

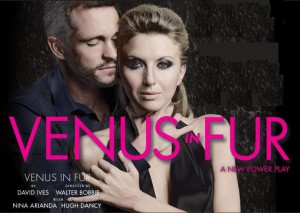

But if reading The New Yorker is not proof enough that these troubling paradigms have hijacked many of our critical responses to artistic experiences, stop by Venus in Fur’s venue, the Lyceum Theater on Broadway, and take a look at the standard review lines. “Broadway’s Hottest Date Night!” raves columnist Liz Smith on the play’s marquee. Better yet, the show’s website – reinterpreting the show dramatically for the sake of ticket sales – presents its tagline “A New Power Play” underneath a blown up picture of Dancy menacingly clutching at Aridanda’s neck. Even Charles Isherwood, the New York Times’ legendary theater critic, writes in an article largely aimed at encouraging Broadway ticket sales that Venus in Fur is a “sneaky two-hander about a sexually fraught encounter between a desperate but calculating actress and a high-handed playwright-director.”

While marketing campaigns seldom offer accurate snapshots of complex works of art, Venus in Fur’s scheme seems particularly poor. Perhaps these blurbs are meant to enhance our experience of the play’s surprising intellectual double-back. More likely, though, they are meant to capitalize on the perception that sexual subversion — in its simplest, most easily accessible form — is enough to attract audiences to the theater instead of the latest Hollywood blockbuster. What it ignores, willfully or not, is the direct implication that Venus in Fur insists upon: that these very assumptions are inextricably linked to political and social identity. When the complexity and honesty of these identities are attenuated by a media that seeks to codify simplistic expectations, we compromise our ability to fully experience art’s greatest political purpose.

This kind of media treatment for a play that resists just these theater stereotypes to its very core seems wholly inappropriate, if only because statements like “Broadway’s Hottest Date Night!” for a show largely preoccupied with sado-masochism is egregiously misguided. But there is a deeper, more troubling problem at hand: because performances — particularly ones that catapult new talent into the spotlight — are undeniably fleeting, we must rely on media, reviewers, and writers as both distributors of information and as critics. Put simply, the media can — and should — uphold as great a responsibility in the production of live art as the artists themselves. Criticism and the media, in other words, should rise to art’s challenges to contribute to a healthier, more organic atmosphere for expressions of political and social identity.

Venus in Fur is, perhaps, an astonishingly adept exploration of the complexities of power and desire as many critics have suggested, but deeper within the text is a more unnerving principle, a question about the confines not just of traditional power structures, but subversive ones, too. As Vanda and Thomas — actress and playwright — play out that great masterpiece of subversive psychosexual fiction, the question that emerges is not what the piece says about men and women, sex and politics, or theater and power. Rather, it asks us to reject these easy dichotomies and look instead towards a subversion that treats its players responsibly, respectably, and — most importantly — as decidedly human. It is this central premise that gives Venus in Fur its vitality: that real, complex, honest-to-god transgression is not easy, and it is not sexy. It is necessary to our very existence.

Elena Gambino is a freelance writer based in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Currently a Master’s candidate in political science at Lehigh University, she studies the political role of arts and culture in building just, healthy communities.

This post may contain affiliate links.