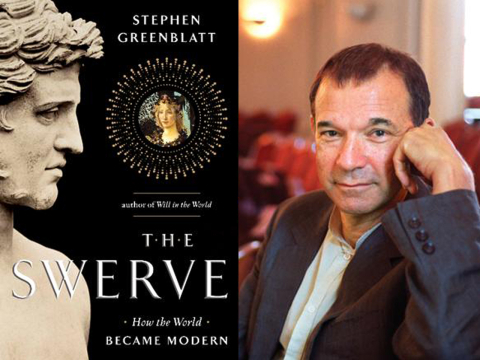

The Swerve: How the World Became Modern

The Swerve: How the World Became Modern

By Stephen Greenblatt

W.W. Norton & Company, 2011

Though the thinkers who have styled themselves, or been styled, “public intellectuals” throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have mostly approached their work with good intentions, the very term “public intellectual” carries with it the specter of elitism it ostensibly aims to banish: the notion that the heady ideas of the academy need an intermediary to translate them – and implicitly, to water them down – into terms intelligible to the masses, terms with obvious utility for wider social life. For fields of study that require a highly complex skill set for basic comprehension, like quantum physics, this is fair enough. My forays into Wikipedia’s quantum physics articles have both reassured me of the site’s editorial rigor and triggered small fits of despair about my own hopeless inability to comprehend calculus.

But for literary and cultural studies, the question becomes more complicated. It’s not that in-depth field knowledge and sharp critical thinking skills aren’t central to humanistic inquiry – they are. But for all humanists’ concern with the relationship between form and content, that relationship is if anything even more absolutely foundational in the natural sciences. You don’t need to have read the Nicomachean Ethics in ancient Greek to become reasonably conversant in the basics and even the nuances of its arguments, but it’s tough to get more than a superficial grip on why the Higgs boson matters so much if you haven’t done math since tenth-grade geometry. In the humanities, then, the public intellectual always courts the possibility of a twofold intellectual faux pas: attempting to present ideas, whether one’s own or those of another, in laypersons’ terms can easily become patronizing oversimplification, both obviously elitist and intellectually irresponsible.

Such is the Scylla and Charibdis that Stephen Greenblatt has taken it upon himself to navigate in the most recent phase of his career. It’s been decades since Greenblatt, a professor at Harvard and arguably the foremost living literary scholar of the Renaissance, has needed any introduction in academic circles. And since the 2004 publication of his New York Times bestselling biography of Shakespeare, Will in the World, Greenblatt has also been on the radar of the general public, or at least that segment of it that regularly reads the Sunday Book Review.

His latest book, The Swerve, finds Greenblatt migrating to the Continent and backtracking almost 200 years. This time around, Greenblatt’s chosen protagonist – fifteenth-century Italian book collector and humanist Poggio Bracciolini – comes nowhere near Shakespeare in terms of cultural capital, but if anything Greenblatt takes on an even more ambitious project here: The Swerve sets out to provide nothing less than a readable, entertaining account of the advent of modernity, framed by Bracciolini’s rediscovery of the ancient Lucretius’ philosophical verse treatise de rerum natura. And though it hasn’t (and probably won’t) hit sales numbers comparable to Will in the World, its narrower appeal didn’t keep it from winning the 2011 National Book Award for nonfiction.

Clearly, Greenblatt has carved out a comfortable market niche for himself in American letters since 2004, into which The Swerve fits nicely. It’s not immediately clear, though, how the rest of his work – the work that propelled him to superstar status within the academy, and ultimately made the publication of Will in the World possible in the first place – fits into that niche, or whether it’s supposed to. The release and reception of Will in the World seemed to formalize Greenblatt’s ascension to elder-statesman status in the academy: the author of multiple landmark texts in literary studies had finally decided to rest on his laurels. He had transitioned (at least temporarily) from the production of specialized scholarship to popular, albeit still erudite, accounts of literary biography and history. In the twenty-first century, only a scholar at the pinnacle of institutional regard could hope to find a reputable publisher for an authorial biography more concerned with telling a good story than with rigorous critical analysis (or, as some of Greenblatt’s harsher critics claimed in 2004, factual accuracy), let alone a biography of the single most written-about author in Western history.

At the same time, however, Will in the World also seemed decisively to signal the end of Greenblatt’s time as a seismic methodological innovator. The book’s reviewers, both academics and journalists, often contrasted its supposed generic traditionalism with Greenblatt’s past work. That work spawned the scholarly movement known as “New Historicism” that has dominated English departments for the past 30 years.

For New Historicist critics, the literary text is not a self-sufficient aesthetic object sealed off from the social world, but an element in a larger network of meaning that also includes non-literary documents and cultural artifacts that wouldn’t traditionally be considered “texts” at all, like the visual arts. The “new” in New Historicism comes partially from its emphasis on the local and marginal as important entry points to the “circulation of social energy” in a culture. While Greenblatt didn’t outright dismiss canonical historical records, he insisted that ship’s logs and diary entries could tell us just as much about their own cultural moments as Holinshed or Plutarch. New Historicism was also “new” in being influenced by the then-recent theoretical work of Marxists like Raymond Williams and by Michel Foucault’s theories of “power-knowledge.” Rather than embodying some unitary, harmonious zeitgeist, literature in the New Historicist perspective participates in the encoding and contestation of power, its dissemination throughout the totality of a culture.

In today’s pathologically skeptical academic culture, the basic tenets of New Historicism come as close to universally accepted doctrine as anything can. But in 1980, when Greenblatt’s Renaissance Self-Fashioning (the earliest systematic example of New Historicist method, though it doesn’t actually use that name) was published, its methods were heterodox. New Criticism, a school dominant in the first half of the twentieth century, eschewed historical context, and it still had high-profile advocates in the early 1980s. New Historicism’s insistence on the social embeddedness of a text flew in the face of the old guard’s formalist dogma; it also arrived just as a sexy, transgressive cadre of like-minded methodologies – feminism, deconstruction, postcolonialism and the like – was beginning to gain real clout. Even in those heady days, Greenblatt stood out for his clear, compelling prose style; he demonstrated that criticism didn’t need to bedeck itself in ten-line sentences and neologisms to be rigorous and innovative.

New Historicism has weathered its share of critiques and still has its discontents, many of them in – ahem – history departments. Though the New Historicist penchant for anecdotes has become a running joke in academic circles, its basic underlying principles still drive many of the books and articles coming out of English departments today. For exactly that reason, it’s a little dissonant for younger academics to think of Greenblatt as an iconoclast, and that may also be why his senescence as a critic in books like Will in the World and The Swerve doesn’t perturb me as much as might be expected. If anything, I find The Swerve’s stealth injections of New Historicism comforting; when Greenblatt argues for the subtle, indirect, yet profound influence of de rerum natura on thinkers from Galileo to Thomas Jefferson, I recall the revelatory fireworks that exploded in my twenty-year-old head the first time I read the 1988 Greenblatt classic Shakespearean Negotiations. A central component of the New Historicist thesis is that culture circulates in ways that aren’t reducible to intentionality, direct influence, or cause and effect; according to Shakespearean Negotiations, there is rather a “shared code” that establishes the materials and limits of representation in ways we might not be able to systematize. Clearly, the “shared code” argument could easily become an excuse for intellectual laziness, but something about the context and delivery of this phrase still makes it seem brilliant rather than irresponsible.

Still, the better angels of my critical nature find the neatness of The Swerve’s historical narrative a bit disquieting. Commonplace in New Historicism is the notion of culture as a holistic, if not monolithic, phenomenon. There’s plenty of room for competing discourses, but all the competition often seems to happen in one big cultural arena. The notion of a “shared code” reflects this presupposition, which also makes its way into The Swerve. Early on, Greenblatt makes a token gesture toward historiographical prudence: “One poem by itself was certainly not responsible for an entire intellectual, moral, and social transformation – no single work was.” Yet that is, more or less, Greenblatt’s argument. In the US, the book is subtitled How the World Became Modern; even more unfortunate is the UK subtitle, How the Renaissance Began. Of course, the general public probably doesn’t want the dozen-plus pages of methodological throat-clearing and caveats that precede many scholarly publications, masquerading as modesty and rigor when in reality they often just eviscerate any of the potentially controversial or interesting claims that follow them. But the grandiosity of The Swerve’s historical narrative also reflects one of the temptations of New Historicism (and most of the other late-twentieth-century –isms): the possibility of a complete, unified explanatory model for the way culture and history work. What makes humanistic inquiry unique and worthwhile is that it doesn’t answer to such models, but few academics would deny that the desire for them can be strong after spending a certain amount of time in the fog of skepticism.

For that reason, I prefer to view The Swerve as a sort of wish-fulfillment with which Greenblatt has gifted his readers – academics in particular – rather than a gesture of condescension. Both Greenblatt and his readers know history isn’t that simple, and he knows we know. But we wouldn’t be reading if we didn’t like a good story, and to have Stephen Greenblatt tell us that story makes it all the better.

Simon Nyi is a PhD student in the English Department at Northwestern University. His research focuses on the early modern period, and he lives in Chicago with his partner and their two dogs.

This post may contain affiliate links.