I woke up Tuesday morning frustrated. No eggs in the refrigerator to cook for breakfast, heaps of work left unfinished, 8.5% unemployed, no healthcare, rising debt, and still no idea of who to vote for in the New Hampshire primary. This last point puzzled me, as I’d been (for want of a better occupation) diligently following the campaign over the past few weeks. I had hoped to be able to waltz into my polling station and inscribe my prized first-in-the-nation X somewhere on a ballot and procure for myself a better future.

I woke up Tuesday morning frustrated. No eggs in the refrigerator to cook for breakfast, heaps of work left unfinished, 8.5% unemployed, no healthcare, rising debt, and still no idea of who to vote for in the New Hampshire primary. This last point puzzled me, as I’d been (for want of a better occupation) diligently following the campaign over the past few weeks. I had hoped to be able to waltz into my polling station and inscribe my prized first-in-the-nation X somewhere on a ballot and procure for myself a better future.

After over a year’s worth of sound bites, media profiles and polls, I was still in the dark. If I’d watched the campaign unfold but could still not grasp the policies of party hopefuls, how was I to lodge a vote in good conscience? I decided to go for a drive and count campaign signs.

35 Romney, 2 Buddy Roemer (who?), 21 Newt, 25 Huntsman, 30 Paul (weighted for size of signs), 0 Santorum, 4 Perry, 3 Obama (Oh, right, the Democratic primary. I forgot). That seemed as good a rubric as any, given the he-who-shouts-loudest coverage I’d so far been given to consider. The truth is, the viability of a candidate is tied to their visibility, and leading up to the primaries and even into them, visibility remains the only measure of any import. The American people are told, and not asked, who’s in the race. The voice of a candidate is amplified by the feedback loop of campaign/PAC dollars and media controlled events with stringent, and self-determined, qualification requirements until it reaches the shrieking decibel that marks the candidate as a ‘contender.’ Has anyone been asked by anyone other than a folksy, on-the-ground reporter at the Fareway whose voice they actually want to hear? Not really, no. Sure, there are the 16 thousand or so who pay the $30 meal ticket price for the privilege to vote in the quaint-sounding “Iowa Straw Poll”. Then comes the hermetically sealed soapbox oratory contest of the caucus which decides… who has the tallest soapbox to stand on going into the primaries?

The nature of these contests does little to stimulate the type of political discourse that would allow Americans to form opinions of party hopefuls. Candidates themselves are trying their hardest just to keep their heads above water long enough to sputter out a few words.

Admittedly, the New Hampshire primary receives the same ludicrous media attention given to those two other events, and there are many good reasons besides why this contest shouldn’t matter as much as it does. To name a few, New Hampshire is a little richer, a little more employed, and a lot whiter than the rest of the country. Two main points, however, set this race apart and make it worth paying attention to. The first is that it has actual consequence, as it sends delegates to the convention. The second is that people, and not cable companies, vote, and they cross party lines to do so. Around 40% of N.H. voters are undeclared, and because of the ease of switching party affiliation in the state, residents can and do vote in whichever primary they deem relevant. Many voters are voting not for the candidate that they want in the Oval Office, but for the candidate whose ideas they think need to be heard.

This means that for the first time the details of a candidate’s platform — and not its relative height — begin to take center stage. Lacking the do-or-die desperation of the general election, votes can here be used to steer debate. Ideas and not electability become the criteria. Add to this the ease with which one can get on the NH primary ballot (a thousand bucks. No petitions. No signatures), and we’re approaching a model for discourse that could help the U.S. break from the two-party lockdown that has homogenized candidates and made radical ideas impossible on either side.

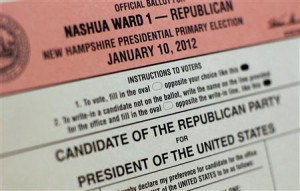

So after an evening of reading up on candidates and reviewing the debates, I shuffled into the fire station, declared my name and felt a twinge of horror and confusion as I requested a Republican ballot. And while I couldn’t mark my X with full confidence in my candidate, I knew at least that I wanted to hear more from him, and had asked myself questions I would not have bothered with otherwise. I dropped my ballot in the box, and then switched my party from Republican back to undeclared. As I left I wasn’t waltzing, but I wasn’t goose-stepping either.

This post may contain affiliate links.