Maybe it’s because I’m 22, unemployed, and living with my grandmother, but lately I’ve been drawn towards narratives that tenderly and carefully map out what it’s like to fail. Sure, Failure with a capitol F is a broad concept, but the many different iterations should ring familiar: there’s no money, there’s no talent, there’s no motivation, etc OR there’s too many obligations, too much temptation, too much that has gone wrong and too many things that inevitably will. This is an extremely common trope, but it’s rare that it’s the only trope. The best failure novels share one thing: they’ve never heard of a happy ending.

Maybe it’s because I’m 22, unemployed, and living with my grandmother, but lately I’ve been drawn towards narratives that tenderly and carefully map out what it’s like to fail. Sure, Failure with a capitol F is a broad concept, but the many different iterations should ring familiar: there’s no money, there’s no talent, there’s no motivation, etc OR there’s too many obligations, too much temptation, too much that has gone wrong and too many things that inevitably will. This is an extremely common trope, but it’s rare that it’s the only trope. The best failure novels share one thing: they’ve never heard of a happy ending.

Hand to Mouth, Paul Auster’s memoir (subtitled A Chronicle of Early Failure), recounting a whirlwind and misspent youth, begins like this: “In my late twenties and early thirties, I went through a period of several years when everything I touched turned to failure” and ends like this: “So much for writing books to make money. So much for selling out.” In between a lot goes wrong – money troubles, a divorce, the death of a parent, struggles publishing, struggles writing – but the closest we get to real failure, the kind that can only be achieved by being embraced, is in a brief encounter with the notorious writer H.L. “Doc” Humes.

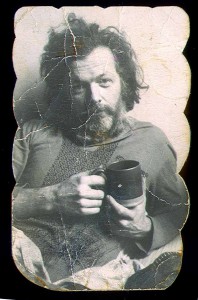

If you don’t know who Doc Humes is, look him up when you get the chance (or read this). Here’s the quick version: Humes, co-founder of The Paris Review, two-time acclaimed novelist, 1950/early ‘60s literary ‘it’ boy slowly trudges deeper into various mental illnesses, giving away his possessions and bouncing between Harvard and Columbia, living in dorms and streets, talking to anyone who will listen. In Hand to Mouth Humes, in the first stages of his breakdown, actually crashes at Auster’s apartment for a week, before eventually wearing out his welcome and moving on to someone else’s couch.

It’s a fascinating story – both Auster’s snippet and Doc’s life in general – mostly because it goes so against the grain of what we have been told the human instinct, especially in America, should be: money, success, power. Auster’s story is familiar – sensitive young writer struggles in his post-graduate years to make sense of his purpose and direction; but Humes’ is so strange that it resonates beyond mere bildungsroman: like Melville’s immortal Bartelby, it echoes, certainly past what our brain would deem logical, through what the heart would deem sentimental, reaching the crevices in our soul that we are never quite sure even exist.

Failure, it seems, in literature and in life, is inevitable. The trouble is not actually the actual act of failing – the trouble is when you hitch your wagon solely onto the star of success. There’s that great quote by Michael Jordon about missing shots, but what gets me the most is something Faulkner said in an interview in Hume’s own Paris Review over fifty years ago. When asked to judge his contemporaries he responded, splendidly, with this: “All of us failed to match our dreams of perfection. So I rate us on the basis of our splendid failure to do the impossible.”

This post may contain affiliate links.