By Elena Gambino

Faced this summer with an unrelenting onslaught of bad political news – manifested most markedly in congressional brinksmanship and frantic economic austerity, bad punditry only made worse by bad policy – I found myself desperately in need of a way to read about politics without overdosing on what feels like a new, nasty, misshapen pill of twenty-first century political debate.

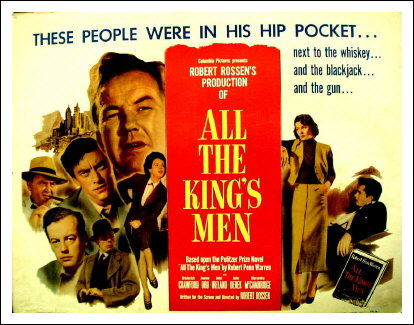

So I picked up Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men, that bastion of mid-century political fiction famous for documenting the nation’s the gradual evolution into modern politics and the public’s decreasing faith in its authenticity and efficacy. If it’s possible to learn from the past at all, I thought, this should tell me a thing or two about what’s going on. I was right.

But what I found was, as is usually the case, more complicated than the answer I was looking for. Our very ability to learn from the past is exactly the kind of relationship of which Warren is most skeptical: at its core, All the King’s Men wonders whether tracing history to learn about the present is even possible in an ever-changing world, and if it is, the novel considers the many ways we can learn from the past “wrong.” But even more than that, All the King’s Men was not, as I had expected, simply a chronicle of the corruptibility of public life and office; rather, this whopping narrative is at its best as it explores our insistent duty to public responsibility despite a world over which we seldom have control.

For Warren, the illusion of the loss of innocence that permeates political debate – that mysterious narrative theme that tells us that things used to be better, that returning to the past can solve problems of the present – is the most dangerous impediment to social responsibility. Instead, All the King’s Men promotes a kind of entering into the world of the present in which common narratives link us directly to our own implication in corruptions of the past but also espouse a commitment to a moral responsibility in the present.

It’s exactly that central purpose – the search for the narrative of a common experience across history – that resonates most profoundly in the context of our current national identity crisis. As Warren puts it, the need for both change and the language of its explanation is “a need to discover oneself on a vast and shifting chart of being.” But before I get to that: a history lesson, as Warren himself would recommend.

Warren writes in his 1975 work “Democracy and Poetry” that, at the heart of our complex social and political lives, and, indeed, at the heart of our conscious selves, is the underlying, if elusive, continuity of history, time and change. The question, he says, is not whether the specific challenges of twentieth century being are new (which they inevitably are), but whether the unavoidable reality of technological progress in the twentieth century represents an irreparable disconnect from the types of esoteric, intuitive wisdoms that had once allowed generations to gain knowledge from across the long stretch of time.

It is a question, to be sure, that extends far beyond its nascent home in literary and political theory. Warren’s 1946 Pulitzer Prize winning novel is rooted as firmly in the reality of the times as it is in its expansive Southern style. Set in the mid-1930s, the novel chronicles the rise and fall of a southern populist politician, Willie Stark, who emerges, eyes a-bulge, touting rhetoric of the common man, from a small rural town to become governor, and, of course, to gradually corrupt his office and his own ideals. He is modeled after true-life Louisiana governor Huey “Kingfish” Long, famous both for promoting leftist populist ideals such as radical redistribution of wealth and massive public works projects, as well as viciously and systematically eliminating his political opponents in legislatures across the state.

Warren’s work, especially All the King’s Men, is colored with what he saw as the increasing public support of deeply corrupt political systems and leaders over morally sound ones, an apparent commitment to “public relations” in politics as a replacement for authenticity and practical idealism, and a decreasing engagement on the part of the public to hold their own institutions accountable. To Warren, with each unnerving trend came a stronger dose of selective memory, a willful ignorance of the influences and lessons of the past. As he puts it in Democracy and Poetry,

Suddenly, change was visible and tangible, and that change was occurring in a constantly accelerating system which undercut inherited sanctions and values in a progressive disorientation of the sense of time and a rupture of all aspects of human continuity.

But, for Warren, the disease of selective memory and loss of faith is a private ailment as well as a public one. All the King’s Men hardly begins or ends with the story of Willie Stark’s public life. In fact, the story of Stark the politician is embedded deeply within the search for self-knowledge and continuity in its narrator, Jack Burden. Willie’s right-hand man and official blackmailer, charged with digging up dirt on Willie’s opponents, Jack becomes increasingly disillusioned not only with his faith in the idealism of Willie’s public system, but with his own self-narrative, his personal implication in what he knows is moral deviancy, and his desperate desire to cut himself off from painful memories of his past. As Willie breaks from his ideological integrity to accomplish his goals with what he views as necessary evils, Jack – a self-proclaimed “student of history” – searches for the meaning in his own experience, and seeks to identify the source of his responsibility in it. It’s clear in All the King’s Men that Jack Burden’s – the individual’s – response to the profound nature of change in the twentieth century reflects Warren’s view of the collective isolation from continuity.

But the private and the public do not remain separate entities for long. In true novelistic fashion (Joyce Carol Oates deemed All the King’s Men guilty of “Hollywood melodrama” in the New York Review of Books in 2002), Willie Stark and his public regime becomes intricately tangled in Jack’s personal history and the people he holds most dear. With the interweaving of the characters’ private lives with the larger narrative of a public regime, Warren creates a kind of double helix that links the barriers to modern selfhood with the corruption of public ideals. Each character in All the King’s Men – Jack, Willie, Adam Stanton, Jack’s childhood best friend and an unrelenting idealist, and Anne Stanton, Adam’s younger sister and Jack’s apparently untarnished first love – are destined to play out the drama of the corruption of established ideals as they look for avenues to maintain their various senses of self and morality.

“The world is like an enormous spider web,” Jack speculates as he begins to recognize the profound nature of the changes around him, “and if you touch it, however lightly, at any point, the vibration ripples to the remotest perimeter and the drowsy spider feels the tingle […].” He continues,

It does not matter whether or not you meant to brush the web of things. Your happy foot or your gay wing may have brushed over it ever so lightly, but what happens always happens and there is the spider, bearded black and with his great faceted eyes glittering like mirrors in the sun, or like God’s eye, and the fangs dripping.

The increasing intensity of Jack’s pessimism is fanned by the “visible and tangible” change that Warren describes in Democracy and Poetry, yet though he can see and feel this change, he is unable to identify its source. Jack has no control over the consequences of his actions, or the actions of others, so the self-constructed narrative of his life and participation in Willie’s regime breaks down completely. As the players in his life spiral closer and closer together, and as Willie’s public administration forces Jack to confront increasingly ugly realities, Jack experiences the “rupture of all aspects of human continuity” that Warren attributes to rapid and undeniable change.

Whatever specific characteristics the novel draws from its particular time and place, though, All the King’s Men is more than a lesson in literary and cultural history. Perhaps more than ever, the anxieties and passions Warren describes are mirrors of our own unique time and place. Where Jack Burden, an insider disillusioned with his self-conscious yet eerily dreamlike descent into corruption and moral hollowness, struggles to reconcile his lost faith in his past with his knowledge of the challenges of the present, a new generation of American citizens in the twenty-first century are coming of age in the shadow of American prosperity and innovation while simultaneously slipping into a climate of intense national doubt.

Consider the status of our own narratives. Our national debate has become more than ever obsessed with the illusion of innocence that Warren rejects. With national policies like budget-slashing, judicial decisions ruled by so-called “literal” interpretations of the constitution, and grassroots movements like the Tea Party all presupposing the innate goodness of the Founding Fathers and their intention, we inch ever-closer to a reality in which it is impossible to take responsibility. These are policies and practices designed to replace the mounting problems of the present with the illusions of the past – the result, then, is a narrative that unrightfully excuses the public for its collective mistakes and allows them to disengage from what they perceive as a hopelessly corrupt system.

As it turns out, Warren presents us with an alternative to this kind of dangerous relationship with the past. Jack’s story ends with his acknowledgment that even despite his lack of control over the vast spider-web of human consequence and implication, his ability to construct a more complete narrative than the excusatory one is redemptive in itself. Only by placing change and corruption on a broader timeline of progress – of looking inward and ahead instead of outward and behind – can we transform them into tools of social responsibility.

It is a lesson that resonates with strains of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1932 speech to the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. “The final word belongs to no man; yet we can still believe in change and in progress. Democracy,” he says, “is a quest, a never-ending seeking for better things, and in the seeking for these things and the striving for better things, and in the seeking for these things and the striving for them, there are many roads to follow. But, if we map the course of these roads, we find that there are only two general directions.”

The directions tend towards either a willful rejection of the realities of the present in favor of an impossible return to an idealized past, or the acknowledgement that, despite the unintended consequences of narratives past and the inevitability of future consequences, man’s greatest ability is to create ever-new faith in the promises of social responsibilities. My lesson was this: we have been given, like Jack Burden, the task of re-imagining our past in order to confront some of the harshest realities in decades. We have, as Americans, extraordinary role models and traditions to draw upon; but as the implications of these realities deepen, we must accept responsibility for them and enter wholeheartedly into the world, as Jack puts it, “out of history into history and the awful responsibility of Time.”

This post may contain affiliate links.