in conversation with Tori Schacht

in conversation with Tori Schacht

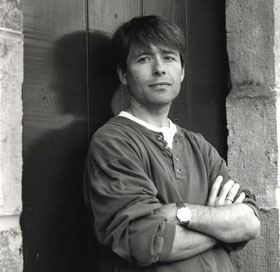

Michael Crummey is a writer we’ve only recently had the joy of discovering in the U.S., but he’s a household name in Canada —and with good reason: Crummey is a poet and a storyteller, and the author of the critically acclaimed novels River Thieves and The Wreckage and the short story collection Flesh and Blood. He has been nominated for the Giller Prize, the IMPAC Dublin Award, Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and won the Commonwealth prize for Canada for Galore.

Galore chronicles about 200 years of life in a fictional village in Newfoundland. A wild, sprawling novel with an unmistakably epic sensibility, the narrative is centered around a generations-long feud between two families: the Sellers and the Devines. The novel’s voice will haunt you, and demands rereading. I reviewed Galore for Full Stop this past spring and on September 19, 2011, I had the pleasure of moderating a discussion with Crummey at 92YTribeca here in New York City. Amongst other topics, we discussed the geographic location of Newfoundland, the politics of incorporating Canadian dialect in fiction, and magical cures for warts.

The sheer amount of historical research that went into this novel is something readers of Galore might not be aware of. But how was the book born? Which came first—the fact or the fiction?

When my previous novel came out in Canada, I was doing a publicity tour and was being interviewed by a guy who worked at a bookstore. I was flipping through bargain books outside the store, and I picked up One Hundred Years of Solitude by Marquez, a book I spent my entire adult life avoiding because I assumed I would hate it; I had this notion that I didn’t like magic realism. It felt like magic realism was a cheat somehow; if anything can happen, a writer has to do no work. But I needed a book for the plane ride, so I picked it up. Before I was even 100 pages into the book I thought, “this is just like home! This is just like Newfoundland.”

It had mostly to do with people’s relationship to the otherworldly, and how matter-of-fact they were about accepting it as a real thing. I thought, there is a book to be written about Newfoundland that does some of the same kinds of things. So I went off in search of the most outrageous, most outlandish stories I could find. Eventually I had to stop doing research, because every time I picked up a book or went into the archives or spoke to someone, I got something else that had to go in there.

For instance?

I was telling some friends in St. John’s about this crazy book I was trying to write. And this guy Tim said “oh, I should tell you about my sister!”

His sister, as a young girl, was afflicted with warts — hundreds and hundreds of warts. They had taken her to doctors and there was nothing the doctors could do. Tim’s mom had gotten wind of a woman on the other side of Newfoundland who was known as a wart charmer. She tracked her down by phone, and the woman asked for her name and age and said, “I’ll take care of this.” The next morning, Tim’s sister woke up and all the warts were loose in the bed-sheets, and there wasn’t a mark on her to say they had ever been there. Tim said they had to shake the warts out of the sheets; there were enough to fill a quart jar.

So this is not a story from someone about something that happened 100 years ago. It’s from a guy my age who grew up just outside of St. John’s. Newfoundland has changed so much in the last generation or two; it’s almost unrecognizable now when you compare it to the world that came before it. But all of that stuff is right there, below the surface. All you have to do is scratch and hit it. I had written a couple of books about Newfoundland when I was living away from Newfoundland, but I don’t think I could have written Galore if I wasn’t living there, sort of being a sponge — picking up the stuff that was all around me.

How does the Newfoundland you’ve known compare to the Newfoundland of yore; the Newfoundland you write about?

The differences are massive. Newfoundland went through a sea change around the time that it joined Canada in 1949. Up to that point in time, Newfoundland had been primarily an oral culture, centered in these tiny little outports that were very isolated from one another. After confederation, it moved to being a written culture. And there have been changes since: there’s now a moratorium on cod fishing, which was really the only reason anyone ever settled in Newfoundland to begin with. In most of those communities there’s no reason for them to exist outside of the cod fishery.

My kids, with the internet, are connected to a larger world in a way that I couldn’t have even imagined as a kid. I was already connected to a larger world in a way that my parents couldn’t have imagined when they were growing up. The world that mom and dad were born into had gone unchanged for a couple hundred years. Then, in the space of a single generation, that world pretty much disappeared completely.

Newfoundland is so distant from the rest of Canada; it’s kind of its own entity. Where are the connections for your Canadian readers, or is it a bit like they’re reading about a foreign country?

Newfoundland’s relationship to Canada has been fairly fraught at times, and Canadians knew almost nothing about Newfoundland for a long time; most of what people knew about it were stereotypes. Newfoundland is like the Ozarks of the country.

What those people thought of Newfoundland had to do with this stereotype of the uneducated, rubber-booted fisherman who talks funny. That has changed in many, many ways in the last 20 years. For instance, a dozen of Canada’s best writers have come out of Newfoundland, and before that it was almost impossible for Newfoundlanders to publish nationally. People are starting to see it for what it is. This book did really well in Canada, where people at least have a starting point. Here in the States I’ve been really interested to see the book finding an audience, because while Canadians don’t know a lot about Newfoundland, Americans know almost nothing.

Newfoundland is a pretty remote, tiny place. It’s so small that it’s amazing it makes any impact on the rest of the world at all. But it really is an interesting place, and that’s part of the reason Newfoundland writers have done so well in the rest of Canada.

Despite being from Newfoundland and having spent most of your life there, you’re somehow able to write about it as someone from outside, who’s passing through and just getting a sense of the place. What do you think gave you this critical distance?

I’ve written obsessively about Newfoundland ever since I started writing. It’s my subject; I’m trying to get it down on paper. The issue of distance is an interesting one. I was born and raised in Newfoundland, but I grew up in a mining town, which was pretty much the geographical center of the island. I was hundreds of miles from salt water — never caught a fish in my life. I get seasick in the bathtub, you know? My only connection to this notion of what I thought of as “real” Newfoundland were the stories I heard mom and dad telling.

We moved to Labrador when I was fourteen, and I eventually ended up moving to Ontario and living there for thirteen years, so for a lot of my life I felt a bit like a faux-Newfoundlander. I think I was writing about it as a way to try to connect to it, to find my place in it. So that distance was something I was born with. Now that I’ve moved home, my sense of what “real” Newfoundland is has changed completely. I can see now how much of that world is in the one that I’m living in, how it’s still just as crazy and wild and awful and beautiful as it’s ever been. The lives of the people around me are still being shaped by the place in the same way. So I feel much more connected to it than I think I ever have. Maybe that means I’ll stop writing about it; I don’t know. Maybe I’ll set my next book in New York.

One of the most salient differences between Part 1 and Part 2 of Galore is in the first section, there are no time indicators—no years are mentioned, no major wars, no historical markers. We don’t even know what century it is. When Part 2 begins, the doctor, Newman, arrives in town, and then little by little there’s this accretion of historical incidents, which ultimately culminates in (the very time-bound) World War I. Why did you decide to divide the novel this way?

What I wanted, particularly at the very beginning of the book, was to give a sense of this happening back in the mists of time. The first settlers in Newfoundland — especially those outside of the main capital area — were kind of rogue communities. It was actually illegal to settle in Newfoundland for years because the British didn’t want to lose control over it; they just thought of it as a floating fishing station. People would all come in the spring and fish, and they were supposed to go back in the fall. But people got sick of doing it, so they would sneak off and stay the winter. We don’t really know much about who they were, or how they lived, or what their story was. I wanted to just give a sense that this was way back there somewhere, before records were kept.

Outport Newfoundland was unique in part because it had so little contact with the outside world. People there lived between two worlds: one was this incredibly stark and often very dangerous physical landscape (particularly the ocean, which was not trustworthy at all), and the other side of that was this netherworld they had created. There was so much in the lives of these people that they had no control over, and in order to deal with that kind of uncertainty they created a netherworld that included superstitions and folk cures and ghost stories. But those two worlds were equally real. The people didn’t make a distinction between them, saying “this is the real world, and that’s just stories that we have.” To those folks those stories had an impact on their lives just as much as the physical world did.

A lot of the book is about folklore and how stories work, so even some of those crazy things that happen in the beginning of the book — by the second section they’re mostly stories. Whether or not they actually happened is irrelevant. As the book progresses, the outside world impinges more and more upon the community. That folk world gets pushed further into the margins. Then you have this [character] who loses his memory in the war, and he’s kind of a non-person—he doesn’t know who he is or where he came from. What saves him, what gives him back to himself are those stories—they tell him who he’s supposed to be. It’s this very circular thing.

One of the things that drew me to Galore was the tremendous strength of the narrative voice. The minute you pick up the book and read, you hear it; it’s unforgettable. How did you develop this voice?

When I sat down and started writing, the narrative voice was there, and it felt like the voice of the book. It’s completely unlike anything else I’d written.

In terms of the dialogue, that was just from growing up around people who spoke that way. There are dozens of Newfoundland accents, so it’s a really tricky thing to do Newfoundland dialogue. A lot of writers from away do it really badly, because they decide to write the dialogue the way it sounds, and it just makes it seem cartoonish. Newfoundlanders are a lot of things, but cartoonish isn’t it. What I’ve always tried to do is to use as much of the language that I can, but there’s also a rhythm of speaking that’s unique to the place. When I’m writing dialogue I try to get the rhythm right, and just leave the accent business out of it. It gives the reader the sense that these people are speaking in a way that is unlike anywhere else in the world, but it avoids that whole issue of cartoonishness when you try to put it down on paper.

What’s in store for you post-Galore? What have you been writing since?

I’ve been saying all along that I felt Galore was the book I was meant to write. I’ve been writing my way towards this book since I started writing, around 17, and it’s kind of a mixed blessing, because now what the hell do I do? I feel like this was the culmination of something, and whatever I do next has to be different. I don’t know if I have “different” in me. So I’m currently avoiding writing another novel, but I’ve been writing poetry again pretty intensively for the first time in 10 years.

I made peace with the notion that my next book is going to be a book of poetry, which is not usually something anyone wants to hear. I remember my mom going to her dentist; he said “I just want you to tell your son how much I love his books, whatever he writes, from here on in I’ll be reading it.” She said “well, he’s got a book of poetry coming out in about a month,” and he said “except the poetry! I’ll read everything else!” So it does feel a bit like a fool’s errand, to be at it, but it’s been a really pleasurable experience. I’ve been enjoying the process of writing poetry, and of relearning how to write it.

Is your poetry as steeped in Newfoundland as your fiction?

It has been, but poetry’s also a lot more personal than fiction. A lot of it is, you know, your day. It’s Newfoundland, because that’s where my day is.

This post may contain affiliate links.