Because I grew up without television, I’m still fairly unacquainted with some of the more significant pockets of popular American brutalism. Of boxing, I know next to nothing. Or knew next to nothing before I sat down and read Avi Steinberg’s essay “Tyson Projected,” published a few weeks ago by n+1 and recommended by the ever on point zunguzungu.

Because I grew up without television, I’m still fairly unacquainted with some of the more significant pockets of popular American brutalism. Of boxing, I know next to nothing. Or knew next to nothing before I sat down and read Avi Steinberg’s essay “Tyson Projected,” published a few weeks ago by n+1 and recommended by the ever on point zunguzungu.

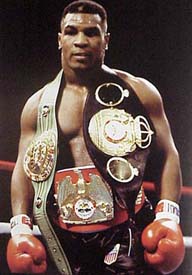

Steinberg’s essay is an enthralling portrait of Tyson, “the last great popular champion of the 20th century” and the inheritor of decades of boxing mythology. It’s long, digressive and fascinated by the eccentricities of its historically miscast subject. The piece begins with biography, following Tyson’s beginnings as a “boxing geek” with a “high pitched-lisp,” but edges, always, toward analysis. Describing Tyson’s tutelage under famed boxing trainer Cus D’Amato, Steinberg focuses on the psychological struggle the program entailed and the divided consciousness the fight requires:

D’Amato inculcated his disciples in his psychological, mystical view of boxing. He believed that a fighter could enter the ring only when he was trained so thoroughly that his body could not fail him; on the other hand, ultimate victory in the ring depended on the fighter’s ability to transcend this training, and rise to a level of courage attainable only in live battle, and only by “the individual struggling against himself.” Only through the trial of combat could an individual achieve full personhood. To D’Amato, who was known to be paranoid, the governing principle of boxing, and life, was fear. Fear was elemental, and could never be conquered: a fighter either thrived on his own fear and used it against his opponent—a trait D’Amato called “character”—or he was dominated by it and folded.

There’s a nice micro/macro wobble to the essay which allows Steinberg to examine the sport as a whole through the career of Tyson. And the man makes a good point of reference for Steinberg’s various riffs on the physical and psychic demands of boxing, the sport’s intersections with the Civil Rights movement, media portrayals of black men. But even in these more maximalist moments its attention is on Iron Mike.

Steinberg’s essay is one of the most interesting pieces of non-fiction I’ve read lately. In it he manages to subject Tyson to some serious scrutiny without reducing the man or his legacy; in the process, Steinberg effects a serious case for the continuous reevaluation of our popular figures, our myths and our myth-makers.

FURTHER VIEWING: James Toback’s excellent 2008 documentary Tyson:

This post may contain affiliate links.