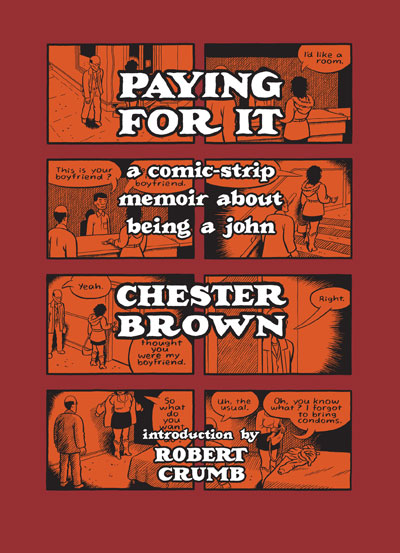

[Drawn and Quarterly; 2011]

By Tim Platt

I’ve received a range of reactions from my friends whom I’ve shown Chester Brown’s Paying For It: a comic strip memoir about being a john. My housemate glanced through the pages and matter-of-factly called it “sad” as he left the room to crawl into bed with his girlfriend. Later–while I was in bed with my girlfriend–she was more frustrated with Brown’s libertarian rants than the idea of prostitution itself. Another friend perked up upon seeing the title, and admitted that he had been considering seeing a prostitute for a while now and was curious to hear the details of Brown’s experience. It’s telling that the gut reactions of my friends who formulate an opinion on the work after only seeing the title and a few pages match up (sometimes verbatim) with Brown’s depiction of his friends, who have been privy to his lifestyle for years.

Since the 80’s, Chester Brown has been one of the mediums’ most prolific and groundbreaking cartoonists. His collection of work ranges from the highly surreal like Ed the Happy Clown[1] to the highly personal like My Mom Was A Schizophrenic. In his memoirs The Playboy and I Never Liked You, Brown shares the effect of pornography in his life and his emotional unavailability towards the women as a teenager. He has made comic adaptations of the Gospel of Mark and the currently unfinished Gospel of Matthew, with one of the most electrifying adaptations of Jesus Christ I’ve come across. Most recently he finished Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography about a Metis leader and Canadian politician who staged two rebellions against the Canadian government in the 1800s.

Paying For It begins with relationship problems. In 1996, Brown’s longtime girlfriend Sook-Yin admits that, while she still loves him, she is in love with someone else. She asks for permission to explore that new love. By 1997 they had broken up, though Brown continued to live in the same house with Sook-Yin and her new boyfriend. The transition from boyfriend to friend was so easy for Brown that he began to seriously question the value of romantic love itself. Brown judged his own reasons for wanting a girlfriend at all as coming from a place of selfishness and possessiveness. “Love,” he eventually concludes, “is about sharing, caring and giving. Romantic love is about owning, hoarding, and jealousy.” Having asserted the meaninglessness of romantic love in his life, Brown had to confront a very big problem. “I’ve got two competing desires,” he tells a friend “the desire to have sex, versus the desire to NOT have a girlfriend. I don’t know how I can reconcile them”.

Brown details his visits with the 22 prostitutes he has visited from 1999 to 2010. He is perfectly blunt. His mind is a mess, full of paranoia and confusion about simple protocol. Yet as he grows more comfortable, his inner monologue begins to sound like the patron of a restaurant trying to get his money’s worth. His thought bubbles are constantly evaluating each separate meeting and the question of the tip is always open.

This inner monologue contrasts with how Brown and each prostitute actually communicate with each other. Brown is complimentary and mild-mannered. He always follows the rules outlined by each prostitute and is never violent. He returns to a few individuals many times through out the memoir, and they all appear to have genuine comfort with each other. Brown is always eager to listen to their stories and perspectives on the trade. “Talking – getting to know the girls a big,” he says, “adds to the whole experience. It makes it seem less cold and impersonal.” His friend Seth responds: “Here’s an idea: if you want a sexual experience that’s not cold and impersonal—get a girlfriend.”

As often as we see Brown with the prostitutes, we see him in conversation with his friends. Brown is always on the defensive. When hearing of his Brown’s first few visits with a prostitute, fellow cartoonists Seth and Joe Matt call Brown sad and accuse him of lacking self-respect.[2] Initially, his friends sound like uninformed reactionaries who have little more argument than that prostitution seems wrong.

Brown’s friends remain skeptical but excited by the gossip through the years of Brown’s narrative. Although the legality and morality of prostitution are in constant debate, the real issue being grappled with by Brown and friends is the legitimacy of romantic love. Brown sees the aggressive possessiveness of romantic relationships and the unrealistic expectations of the romance ideal as “evil”. He even investigates the advent of romantic love poems in the 12th century and concludes that romance was always an abstraction about feelings towards God, not feelings between two human beings. With a worldview centering on the idea that romantic love is destructive, Brown sees prostitution as a healthy way to experience sex and intimacy. Though this is point is well argued, Brown’s feelings towards certain women he sees regularly border on romantic. His real emotions and his philosophical stance are not always in sync.

Brown’s narrative leaves room for ambiguity with regards to the romantic love vs. prostitution debate. His 50 pages of appendices and notes, however, argue his political stance point by point–citing personal research as well as conversations with prostitutes he knows. He takes on every argument he has heard against the legalization of prostitution and provides his response. For the most part, Brown’s arguments are strong, well researched and passionate. He tends to fall back onto libertarian talking points about individual autonomy in the face of the government a little too much for my taste, but it is still interesting to read his thoughts.

The seriousness and honesty Brown brings to the topic of prostitution is inspiring. His grounded paneling and sparse illustrations facilitate well a work constantly in conversation with itself. In Paying For It, Brown is–as always–a brilliant cartoonist, a skilled memoirist and an engaging thinker.

[1] The 1990 Harvey Award Winning Graphic Novel has a scene in which Ed’s penis is surgically replaced with the head of Ronald Reagan.

[2] Brown’s Response: “The guy who has self respect doesn’t need to be in a romantic love relationship. The guy who’s paying for sex isn’t using sexual relationships to shore up his fragile ego”

This post may contain affiliate links.