Elizabeth Bishop

[Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011]

Prose

Elizabeth Bishop

[Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011]

by Anna-Claire Stinebring

To discover the poems of Elizabeth Bishop is to be transported. To lushly rendered geographies, certainly, but also away from the expectation that modern poetry is an either/or affair, a winner-takes-all competition between tradition and innovation. In Bishop’s poetry, fearless experimentation and mastery of traditional poetic form are not mutually exclusive. Bishop’s hybrid approach can feel liberating; it could also make new readers uneasy, leaving a lingering sensation of not quite being in the know. The reissue of Bishop’s collected Poems and Prose by Farrar, Straus and Giroux at the centennial of her birth is an opportunity for new readers to discover her work. After all, Bishop’s poems hinge on the experience of discovery, a discovery that demands awareness, not preparation.

* * *

The four original books of poetry Bishop published in her lifetime, North & South (1946), A Cold Spring (1955), Questions of Travel (1965), and Geography III (1976) encompass locales at once exotic and familiar: Paris and Florida; Mexico and Brazil; the recesses of memory. The opening poem of the collection Questions of Travel, “Arrival at Santos,” immediately registers the dissatisfaction of the traveler: “Oh, tourist,/is this how this country is going to answer you/and your immodest demands for a different world…?” The tourist in the poem is wired to transform even the most unpromising landscape into “scenery,” and to feel estranged by the mundane details, such as postage stamps with faulty glue and pale soaps. “Finish your breakfast” the poem then commands the traveler, who is so impatient for revelation. “Arrival at Santos” encompasses the monotonously human—even lovingly inventories it—and then upends it. At the poem’s end a new order is suddenly announced, primal in its plainness: “We leave Santos at once;/we are driving to the interior.”

Questions of Travel is divided into two sections, “Brazil” and “Elsewhere.” The fecund Brazil the reader wades through for the rest of the first section is marked by a consistent refusal to idealize and a razor-sharp attention to detail, as is the elegiac “Elsewhere.” Bishop lived in Brazil for an extended period, moving beyond the tourist stage but remaining an outsider. Not easily traveled, Bishop’s Brazil is everywhere invaded: by the Portuguese “in creaking armor”; by “too many waterfalls” that leave the mountains “slime-hung and barnacled”; by a rainy season that embellishes a wall with “the mildew’s ignorant map.” Bishop refuses to go beyond what is there, though what is there always includes the experience of perception, which can be highly subjective, even surreal. And when insight appears, it breaks out abruptly, with a calculated artlessness that mirrors experience.

“A Cold Spring” opens the collection of the same name with an epigraph by Gerard Manley Hopkins, a favorite poet of Bishop’s: “Nothing is so beautiful as spring.” Bishop’s poem respects this statement, but pushes it, too, with her investigative approach to beauty:

Finally a grave green dust

settled over your big and aimless hills.

One day, in a chill white blast of sunshine,

on the side of one a calf was born.

The mother stopped lowing

and took a long time eating the after-birth,

a wretched flag,

but the calf got up promptly and seemed inclined to feel gay.

The simplicity of the description of the hills and weather amplify the “wretched flag” and the off-kilter “inclined” given to the calf. The next stanza begins

The next day

was much warmer.

What is this? These two lines are audaciously dull, and would be inexcusable if they weren’t the set-up and the follow-through for lines deeply original in their detail and syntax. Soon to follow in the poem are dogwood blossoms, “each petal burned, apparently, by a cigarette-butt.”

* * *

There’s something about Bishop’s method of description that is sympathetic, but in a way that knocks the wind out of you. The poem “Manuelzinho” addresses “the world’s worst gardener since Cain,” and also offers a quiet apology to him. “Florida” delineates a savage, murkily beautiful world in which the “monotonous, endless, sagging coast-line/is delicately ornamented.” In the later poem “Crusoe in England,” Crusoe recites a double loneliness: that of exile and of returning to civilization. Yet Bishop’s poetry, so centered on loss (“Oh, must we dream our dreams/and have them too?”), retains a steadfast faith in the details of life, consistently imperfect but full of the dazzle of discovery in their strangeness. In “At the Fishhouses,” for example, it’s the herring scales lining fish tubs and wheelbarrows “with creamy iridescent coats of mail” that reproduce that shiver of discovery. Later on in the poem, the speaker pauses to sing Baptist hymns to a seal, and the framing of the interchange cannot be anticipated: “He was interested in music;/ like me a believer in total immersion.”

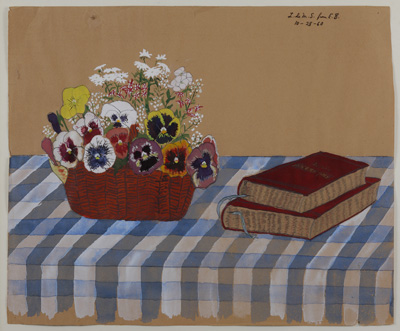

There’s an accuracy of sentiment to that image, even if the statement is preposterous. Its precision lies in a commitment to a particular way of seeing, itself stubbornly subjective. Bishop was fascinated by untrained painters, as attested to in “Large Bad Picture,” “Poem,” and a profile in Prose of a Cuban painter in Florida, Gregorio Valdes: “He managed to make just the right changes in perspective and coloring to give it a peculiar and captivating freshness, flatness and remoteness.” Painters like Valdes, with their obsessive and even magical rendering of the subject (painting every blade of grass at the expense of the overall picture), are a basis for Bishop’s own theories of sight, and of the urge to capture what is seen. It is an almost religious compulsion. “Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance” is another poem centered in the boundless desire of sight and its inadequacies: the desire to have been able to see the profound as it happens, to have “looked and looked our infant sight away.”

In “Poem,” Bishop reveals how the family relic of an oil painting, lumpy and dull, can still transport the viewer to untapped memories and lost places (the “yet-to-be-dismantled elms”). As the title indicates, the crude painting becomes a synecdoche for the larger impulse to transfer experience into art. The effect of the painting on the speaker in “Poem” is the same as Bishop’s aim in her poetry. The difference, of course, is that Bishop always knows exactly what she is doing with each additional blade of grass, so to speak. This is most evident in her use—and decision not to use, depending on the poem—sophisticated rhymes and traditional poetic forms.

Two of Bishop’s most famous poems, “Sestina,” and the villanelle “One Art,” employ difficult traditional forms originating in the courts of medieval France. A villanelle has six stanzas ruled by two rhymes and two refrains, creating a lulling insistence to the poem. In “One Art,” the repetition and subtle variation of the refrain intimates doubt where there is the pretense of certainty. A sestina is comprised of six stanzas of six lines each. The end words of the six lines of each stanza are the same, but they reoccur in a strict rotating progression (the end word of the first line of the first stanza becomes the end word of the second line of the second stanza, and so on). The poem ends with a three-line envoi, which also uses all six words.

“Sestina” signals with its title the form the poem takes. A sestina is such a specific and peculiar form that you might assume Bishop is bragging with the title: that she is advertising her accomplishment. On closer inspection, however, one finds the opposite to be true. The straightforwardness of the title matches the haunting austerity of the poem, as well as the poet’s refusal to veer towards the sentimental. House, grandmother, child, stove, almanac, tears: through the cyclical repetition of these six words the domestic entities become incantatory, and the humblest and most old-fashioned of rooms becomes a landscape expanding with what’s not said.

* * *

The heart of the new Prose is the first section of stories and memoirs, including a memoir of Bishop’s formative friendship with the poet Marianne Moore. Much of the fiction and autobiography in the opening section of Prose mirror Bishop’s poetry in content and style: the earliest stories have a riddle-like quality similar to poems in Bishop’s first book, North & South, and the story “In the Village” is very similar in perspective to later poems, including “Sestina.” “In the Village” is set in a spare Nova Scotia childhood (Bishop was partially raised in Nova Scotia by her grandparents). The child’s view of this world is perceptive and inarticulate in equal parts. The brief “To the Botequim & Back,” a sliver of life in Brazil only slightly larger than a poem, employs Bishop’s same kick-in-the-guts brand of compassion, as she catalogs extreme poverty against the richest of landscapes.

Two essays in the new Prose are windows onto Bishop as a young writer, partially illuminating the development of a singular voice. In the essay “Efforts of Affection: A Memoir of Marianne Moore,” Bishop charts her long friendship with her whimsical, prudish, brilliant, stubborn, delightfully exasperating mentor. Moore is as uncompromising and idiosyncratic in all aspects of life as she is in her poetry:

I never left Cumberland Street [Moore’s residence] without feeling happier: uplifted, even inspired, determined to be good, to work harder, not to worry about what other people thought, never to try to publish anything until I thought I’d done my best with it, no matter how many years it took—or never to publish at all.

Any writer currently in despair over their menial job/unpaid internship/latest rejection letter/all-of-the-above might want to tack this above their desk. I equally recommend Bishop’s “The U.S.A. School of Writing.” In this memoir of post-graduate life, the young Bishop is roped into the kind of comically bad job that is only endured for the brilliant personal essay (sweet revenge!) to follow. The position involves impersonating an instructor at a correspondence writing school of dubious legality. Most of Bishop’s epistolary students in “The U.S.A School of Writing” are cowboys and cooks who are part-conned, part-consoled by the ludicrous school. Bishop concedes that most of her students are hopeless as writers, but she inventories a few vivid exceptions:

His stories were fairly long, and like Gertrude Stein, he wrote in large handwriting on small pieces of paper…. He characterized everything that appeared in his simple tales with three, four, or even five adjectives and then repeated them, like Homer, every time the noun appeared. It was Mr. O’Shea who wrote me a letter that expressed the common feeling of time passing and wasted, of wonder and envy, and partly sincere ambition: “…I am thinking of being able to write like all the Authors, for I believe that is more in my mind than any kind of work.”

Against the backdrop of the seamless “Sestina” or “One Art” with its strategic seams, much controversy has rightfully arisen over the inclusion, in recent collections of Bishop’s work, of poems Bishop chose not to publish in her lifetime, as well as scraps she probably did not consider poems at all. Bishop was an uncompromising perfectionist, and the debate over these poems is crucial to her legacy.

The new Prose includes some unfinished essays and also blurbs. Since prose was not Bishop’s primary medium, the jumble is less worrisome. Still, it is symptomatic of the same problem: a kind of hero-worship that veers toward the condescending, as it affirms everything the writer ever scribbled down. What I object to is the editor’s decision to mix the starts and blurbs in with the completed essays, so that readers stumble onto them without warning. In the section “Essays, Reviews, and Tributes,” for example, diffuse notes that Bishop apparently used for a lecture follow a book jacket blurb for Robert Lowell’s Life Studies. After this comes a polished review of Marianne Moore’s own collected poetry and prose, which includes a long discussion of Moore’s refusal to include anything that failed to meet her uncompromising standards. The Life Studies blurb is incisive and the notes are thought provoking. Yet the failure to identify, introduce, and offset the inconclusive from the complete denies a natural hierarchy to a writer’s life work.

Culling material first published in the controversial posthumous Bishop collection Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments, edited by Alice Quinn, the new Poems includes an appendix of “unpublished manuscript poems” transcribed with accompanying reproductions of the original drafts. There is merit to seeing some of Bishop’s working process on pages densely hatched with added and crossed-out lines. These drafts illustrate the rigor and restraint in editing that many have felt was not given to Edgar Allen Poe. I’ll leave this debate to the experts on Bishop, but I did find it suspect that some of the reproduced “manuscript poems” are crossed out entirely, while others have no corrections at all. Compare this to the many tortured, prosy drafts of “One Art,” which finally emerged a masterpiece. The white space around the painstakingly crafted lines glows, speaking to what can neither be said nor suppressed.

This post may contain affiliate links.