[University of Iowa Press; 2011]

[University of Iowa Press; 2011]

by Sam Rowe

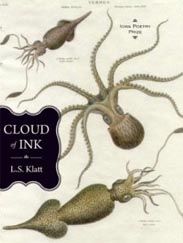

L. S. Klatt’s Cloud of Ink, one of the two winners of the 2010 Iowa Poetry Prize, is a solid volume of eccentric, dense, whimsical, occasionally inscrutable and occasionally gorgeous poetry. Cloud of Ink is Klatt’s second book, coming on the heels of Interloper, winner of the 2008 Juniper Prize for poetry. Though the collection is somewhat eclectic and adopts a number of different approaches, Klatt’s talent for imagining bizarre, dreamlike scenarios is certainly one of his greatest strengths.

Many of his poems start with a “what if” conceit that is used to generate vivid imagery, perhaps modulating, as the history of the conceit would seem to demand, into metaphor. But perhaps not—the nutty ideas themselves may be ends rather than means. Case in point, “The Pear as a Wild Boar”, whose title says it all: “The hunter, who spent the better part of an afternoon / tracking spoor, now comes upon the wounded pear / & puts fingers to neck / &, feeling / the pace of its breath, slits its throat.”

Given Klatt’s well-developed chops for the whimsically strange image, it comes as something of a surprise that place and geography also figure prominently in Cloud of Ink. Poems such as “Ohio” and “Semiconductors in the Breakbasket” offer a refreshingly zany alternative to James Wright’s dour visions of the American Midwest. In the former, Klatt imagines elements of the titular state’s industrial landscape transforming into William Carlos Williams’ famous wheelbarrow-side poultry: “I worry about your fences / wherein thousands of propane tanks / stand breast to breast / like white chickens.”

Yet another voice comes through in a handful of more tranquil poems. Continuing the Midwestern theme, the brief narrative poem “George Keats” tells the story of the title character’s immigration from England to Ohio in the nineteenth century, and of his daughter’s subsequent suicide. The poem starts off characteristically wacky (“How beautiful are the keyholes / in the wrists of brother Keats”), but then settles down into stately, elegant narration. George Keats, by the way, was the younger brother of the Keats—Klatt’s poem recovers an incident on the margins of literary history and makes it speak. The lovely “Broadcaster”, on the other hand, speaks for itself: “And let it be said that our Royals were once smeared / with indigo / & that the deft, in response to Depression, / descended into violet, / ascended as ultraviolet.”

Klatt’s verse is, with a misstep here and there, vibrant and well-crafted, but the real interest in these poems lies in their attempts to reimagine the work that poetry does (to distort its formal constraints, relation to its subject matter, relation to other poets’ work, etc.). It seems to me that the conceit, the wacky “what if” idea, is ultimately the germ for Klatt’s poetic energy. Yet if the poems are ever unsatisfying, it is because they become a bit too invested with their own droll innovations. A handful of poems like “Frontiersman” (a meditation on space-traveling antelope, or something) careen dangerously close to the boundary between whimsy and cutesiness. That said, I’m inclined to cut any poem that that errs on the side of bizarrerie rather than stolidity some slack. In fact, the poems that stayed with me the longest after I put down the book (excepting the above-mentioned “Broadcaster”, which really is gorgeous and is certainly the highlight of the collection) were the ones that seemed to overreach themselves in some way, to gesture towards a larger, stranger idea than their form was quite able to contain. I, for one, hope Klatt builds on his recent successes in the poetry prize circuit so we get to see more such overreaching.

This post may contain affiliate links.